By Lisa Conway

I will begin this post by mentioning that Rebecca Bruton is an acquaintance of mine – we both did our undergraduate at York University years ago, and our paths continued to cross in several shared circles. I even recently worked on the mix for one of her film scores. It is of course possible to have talented friends, and friends who make work you admire and want to write things about, and after discussing the singular yet very much classically-minded scores of Nicole Lizée, it seemed fitting to explore Rebecca’s pieces that are handwritten, durational, graphic, and often open / indeterminate.

Rebecca Bruton. Photo Credit: Sarah Lianne Lewis

In addition to her composition practice (which has included writing for Quatuor Bozzini, Arraymusic, and Continuum Contemporary Music as part of the join CMC/CLC/Continuum project PIVOT), Rebecca also has an active and varied performance practice as violinist and vocalist, and releases songs under the moniker Rebecca Flood. She holds a MFA in Music Composition from Simon Fraser, where she mounted a highly ambitious multi-disciplinary song cycle, Sugar’s Waste, as her thesis piece, as well as co-founding Tidal ~ Signal, a festival celebrating sound art and experimental music by women and transgender artists in her spare time.

With no shortage of things to talk about, I decided to focus in on a particular string quartet as a jumping point for our conversation – a piece titled All I dreamt; twice as much composed for Quatuor Bozzini last year. Fun fact : my cat Inky is not as into this piece as I am.

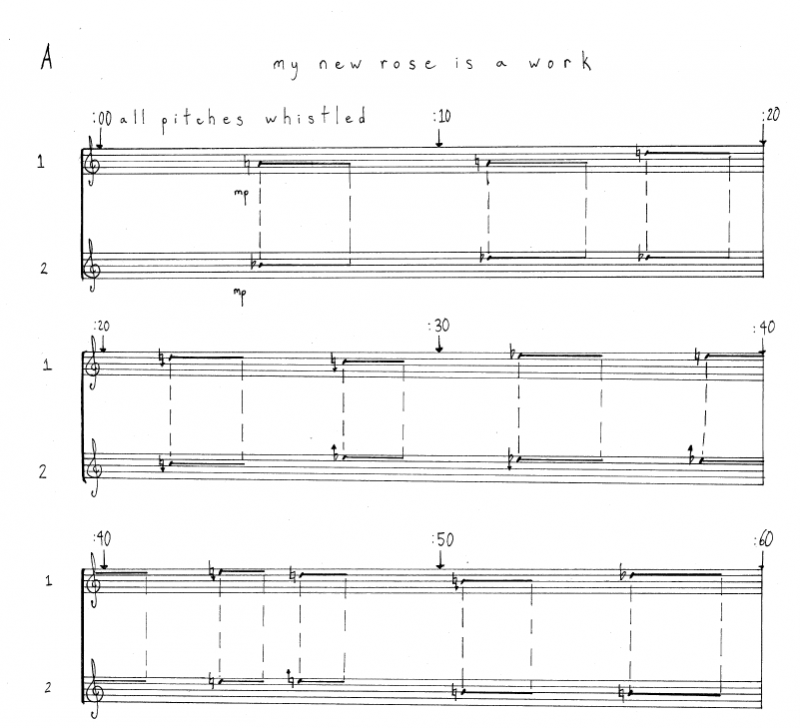

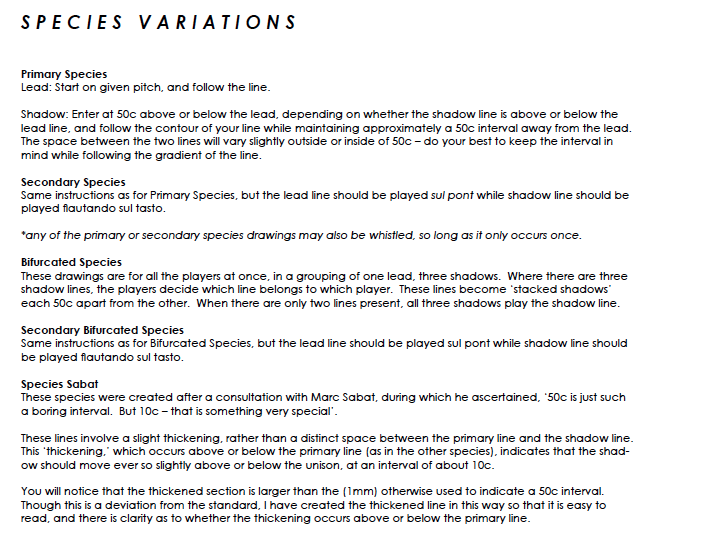

The score is open, yet highly specific, including pages of instructions specifying inspirations for the piece (including David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and a recording of her grandfather’s Swiss music box), suggestions on violin and vocal tone and improvised sections, as well as how to go about moving through the movements. The titles of each section are borrowed from the poem “a rose is a rose is a rose manhattan,” by Nikki Reimer, which is included in full at the end, and performers are even instructed to cut up part of the score to create a shuffleable deck of cards (to be attached to cardboard before the performance). I haven’t even got to mentioning that the entire first movement is whistled – a pretty punk rock move in my opinion.

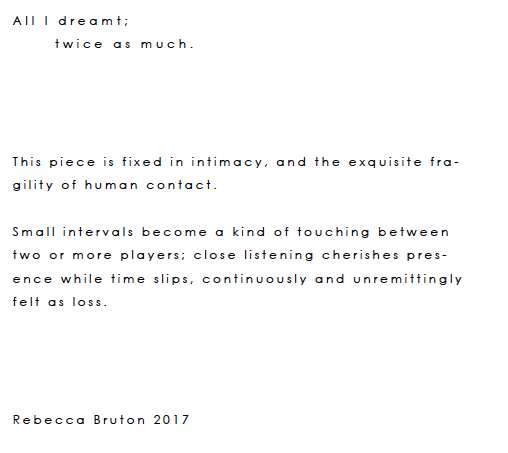

Excerpt from All I dreamt; twice as much. Copyright Rebecca Bruton

Rebecca and I had a phone chat to discuss this piece, her process, and creative practice in general. It is important to note that Skype was being temperamental that afternoon, so we were forced to resort to talking on the phone and I was unable to get a recording of the conversation for my future reference. As a result, writing this post involved much deciphering of my scrambled notes, and paraphrasing of Rebecca’s eloquent answers. Much of our conversation was centred around artistic learning and growth, and the often strengthened results birthed out of creative problem solving, so perhaps all our technical strife was a fitting part of the journey, and a challenge I should embrace and aim to rise to.

I began by asking Rebecca about choosing to have openness and indeterminate sections in her work – is this something that has gradually developed over time or was it a conscious decision?

This led us to a discussion about the concept and tension of “ownership” in composition – Rebecca grew up playing in various groups and punk bands, where the creative process is often communal and there is a sense of shared ownership. Inviting performer input and encouraging a collaborative environment is a natural extension of Rebecca’s musical origins. In addition, a score of this nature gives her the chance to work more directly with people in what is often a solitary musical practice (composition), and participate in the “social activity” of music-making, a part of the process which brings her much joy. She’s also found that by “inviting musicians to be themselves” – ie. by exploring who instrumentalists are as humans as well as instrumentalists, and incorporating that into the work – the results are stronger and more interesting.

Her preferred approach promotes learning and growth as a creator, and often involves what Rebecca called “collaborative problem solving,” which can involve highly stressful troubleshooting close to the performance date. It’s a fruitful process if one can rise to the challenge – by working closely with a clarinetist in Arraymusic, revelations and essential revisions were made in a section exploring multiphonics. She also pointed out the excellent opportunity one has as a chamber composer to work with musicians that are technical masters of their instruments, stating “it is such a gift when players can do ANYTHING you ask of them, technically.”

Rebecca was describing her process as involving the conscious decision to always “leave something open to failure” in her scores, almost creating puzzles for herself to solve. Though the term failure often has a negative connotation, it is rather the opposite in this instance – much like incorporating chance operations or experiments, embracing human input pushes Rebecca creatively, allowing her to come up with material she wouldn’t have otherwise. This sort of collaboration births new closeness and energy between musicians, a newfound intimacy.

We talked candidly about the challenges of open yet intricate scores – ample rehearsal time is vital. Being granted enough time to work with an ensemble is a challenge for most commissioned composers, and extra important when one’s score involves numerous pages of instructions, and specific graphic interpretations. To the casual observer, Rebecca’s scores appear sparse and as a result might register as simple and sight-readable; however, the pieces involve a deeper sort of preparation and full internalization of the text, much more than just “playing the parts.” Due to the bias towards conventionally complex notation, she has to be assertive to be granted enough rehearsal time, ensuring a smooth performance.

I think I mentioned in the beginning of this post that Rebecca’s scores currently are all handwritten, which was something I was curious about. Was this something that came out of her PIVOT mentorship with composer Chiyoko Szlavnics? (Szlavnics has made some really beautiful graphic score-like drawings)

The answer is no, although studying under Szlavnics was a good reminder that if one chooses to handwrite a score, it needs to be done extremely well. Part of Rebecca’s decision to handwrite was made out of practicality – it provided a more concise way to express certain sounds and gestures, while keeping things musical. Though Rebecca expresses a lot of enthusiasm for the craft and tradition of engraving and making manuscripts, she firmly believes there is no point in handwriting something if you can do it better in notation software.

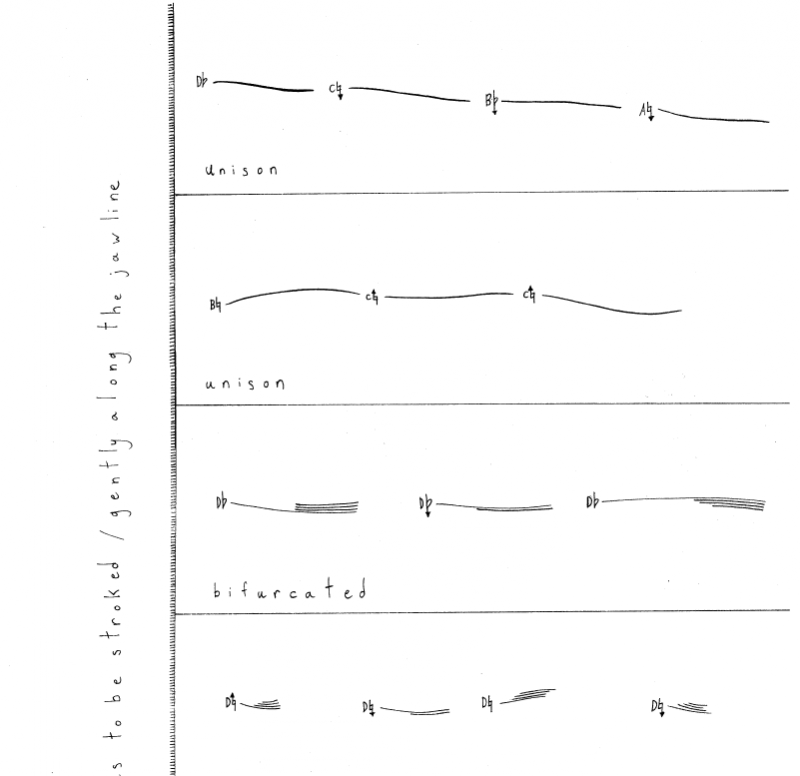

“People respond differently to a handwritten score,” she reflects, adding that initially she was worried about not being taken seriously, but Szlavnics strongly encouraged her, pointing out that handwritten scores are becoming more in-demand as performers begin to recognize a loss of the composer’s individual expressiveness as we move towards digitized score uniformity. Incorporating text and graphics in her compositions has often proved more straightforward and easier to understand – in All I dreamt; twice as much, outlining gestures in the microtonal section iii using note names and line drawings yielded more musical results, compared to more mathematically accurate methods.

“Though less specific mathematically, it was more specific musically .. [the graphic] allowed better listening”, she states, adding that she often finds it easier to communicate her sonic vision through words and text rather than music. In rehearsals, she frequently turned to visceral descriptions, narratives, or metaphors to direct the ensemble, and eventually began to incorporate this into the scores themselves. In All I dreamt; twice as much, text instructions advise that “the feel of improvised melodies is gentle and exploratory, reminiscent of a three-year-old who is sitting in a shopping-cart while singing a meandering nonsense story. The child is audible, but only very slightly comprehensible.” Later on, the violin is instructed to play with an “almost-satirical vibrato,” with the cello residing “in similarly sentimental territory.” Words obviously hold importance for Rebecca – the opening lines of the score are a poem in itself.

Excerpt from All I dreamt; twice as much. Copyright Rebecca Bruton

Excerpt of the accompanying text instructions for the previous graphic section. Copyright Rebecca Bruton.

Opening lines of All I dreamt; twice as much by Rebecca Bruton

As someone who actively incorporates technology into their practice, I somewhat selfishly asked about Rebecca’s experiences incorporating electronics and Max MSP. She works closely with programming whiz Paul Paroczai – who builds her custom patches based on her descriptions of timbre, sonic palette, and overall vision for the piece. Fascinated by the ways electroacoustic pieces work temporally and formally, as well as ways in which to transcribe electronic sounds by ear, Rebecca embraces the sometimes unpredictable outcome of blending acoustic and electronic elements – the collaborative give-and-take encourages her to respond “in a creative way”. She is a generous collaborator, acknowledging the importance of being realistic in expectations, and valuing the time and contributions of others.

My final questions to Rebecca involved her songwriting practice – does it all stem from the same place? How does one balance a multi-faceted and varied artistic practice? Her MFA was based around her songwriting work, but in the final 90 minute “song event” there were only a few songs interspersed with instrumental movements, cassette tape looping, explorations of feedback, and a noisy string quartet. It seems Rebecca has found a sense of belonging in the chamber world: “What I like about working as a chamber music composer is the total openness of form … you can do anything you want as long as you stand by it,” and she is increasingly confident bringing elements of her songwriting practice into that world. Perhaps it has always been there, even abstractly, providing an emotional thread and underlying narrative in her work. “When I feel like I have to be a composer, [the music] isn’t good,” she mused, noting she’s moved towards just “allowing things to exist” without labels or boxes or genres.

Though she is increasingly getting more commissions from chamber groups, I think we’ll still be hearing some stunning songcraft from Rebecca Flood in the future.

Lisa Conway is one of the 2018 CMC Library Artists in Residence and will be contributing a series of blogs profiling works by Canadian composers.