Part 6 / Text Pieces

This is the sixth and final excerpt in a series that explores Gayle Young’s musical practice, drawn from the interview that took place with Camille Kiku Belair on December 14, 2017 at the Canadian Music Centre in Toronto.

In this excerpt we learn how Gayle began integrating technical understandings of acoustics into her vocal writing, and how she began to engage with the multifaceted complexities of text and vocal performance. Her interest in acoustics was encouraged by a newly-arrived professor at York, James Tenney.

CB: When did acoustics become a priority in your composing?

GY: That began very soon after I started studying music at York. In a musicianship class Bob Witmer pointed out that the higher overtones of a trumpet are out of tune with a piano, so trumpet players have to adapt to this in their playing. That was the first time I understood that the tuning I’d learned as a pianist was not the only possibility.

CB: When did vocal acoustics become a priority in your composing?

GY: While I was still at York I began researching the overtones of vowel sounds in the science library. Jim Tenney had begun teaching there during my last year, and I was in the contemporary music ensemble that he directed. When I told him about the research he loaned me some research papers from Bell Labs that provided detailed information about the frequency bands that define vowels.

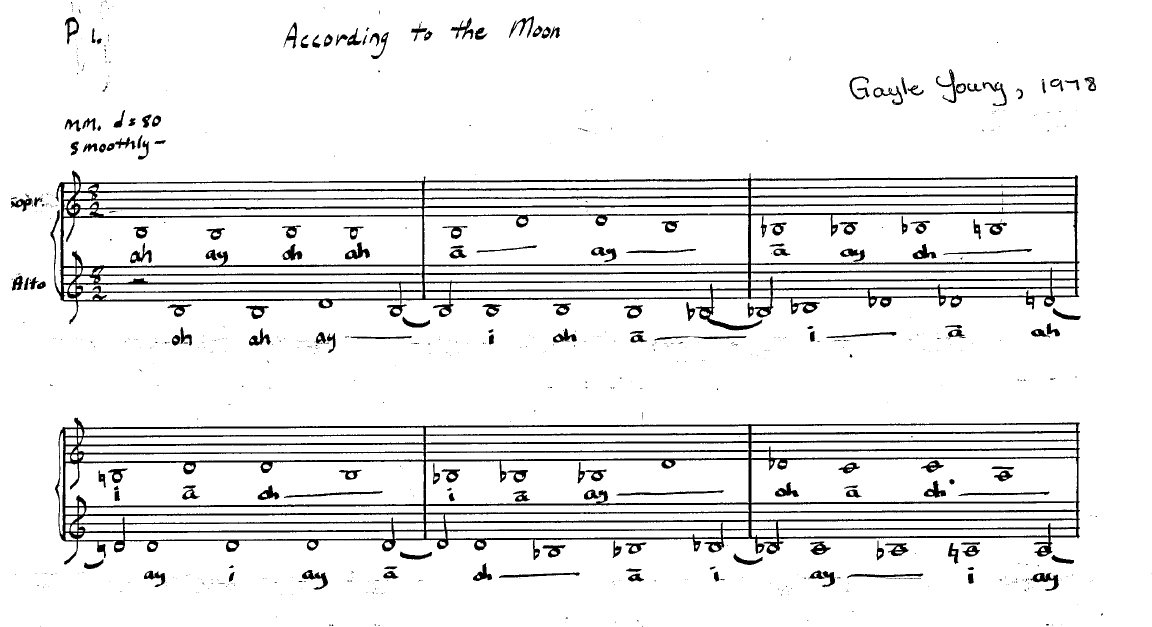

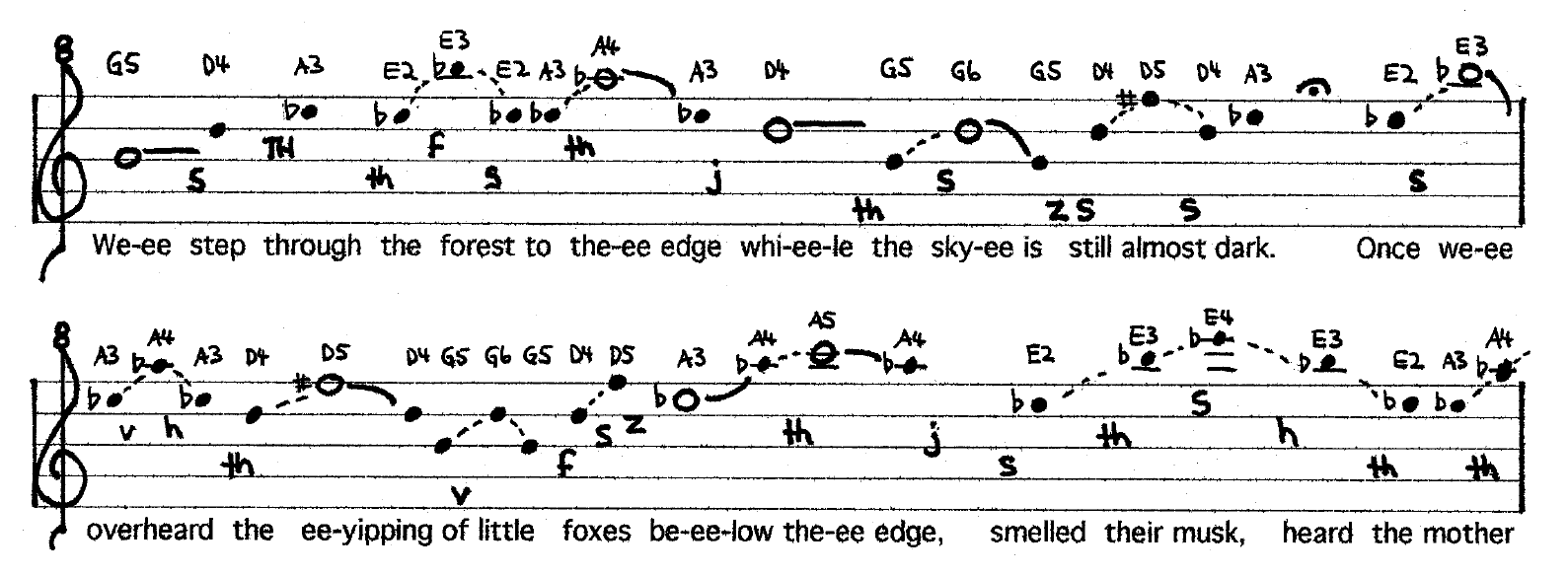

A score excerpt from Gayle Young’s According to the Moon, copyright Gayle Young.

CB: How did you work with this in a composition?

GY: The first piece I completed was According to the Moon, commissioned by visual artist Reinhard Reitzenstein in the late 1970s to be played into his installation piece. It’s a long duet for soprano and alto voices, using sustained vowel sounds but no words. It’s a challenging piece and I recorded it in sections at the Music Gallery. It wasn’t performed live until a few years ago when Sarah Albu programmed it for four singers and instrumental backup in a concert she organized at The Hague in the Netherlands. With four people singing, not always at the same time, there was time for people to catch their breath.

In talking to you about this, I realize the essential idea is related to what Bob Witmer told us about the trumpet. During the research phase I learned that the notes sung by sopranos are sometimes in the same register as the formant bands that define vowel sounds. This makes it hard for listeners to distinguish the vowels, so singers, like trumpeters, have to adapt constantly. In According to the Moon the notated pitches are below the lowest formant bands, so as the registers change the vowels change with them. I decided on a rather restricted set of counterpoint rules for this piece, and using that system I built an arch form, beginning and ending with the two parts almost in unison.

CB: Did this lead to a new way of composing?

GY: Yes… I’ve recently integrated vocal formant bands with soundscape in Cedar Cliff, a six-channel pre-recorded piece commissioned by visual artist John Noestheden for an installation last summer at Rodman Hall in St. Catharines. I filtered recordings of a forest in a light rain according to the formant bands of the three vowels that don’t change over time. The ‘ee’ came from one corner of the space, the ‘ah’ from another and the ‘oo’ from the third set of speakers – not constantly though, the different vowel formants faded in and out. A listener would move from one area to another and in the centre would hear all three vowels within the sound of the forest.

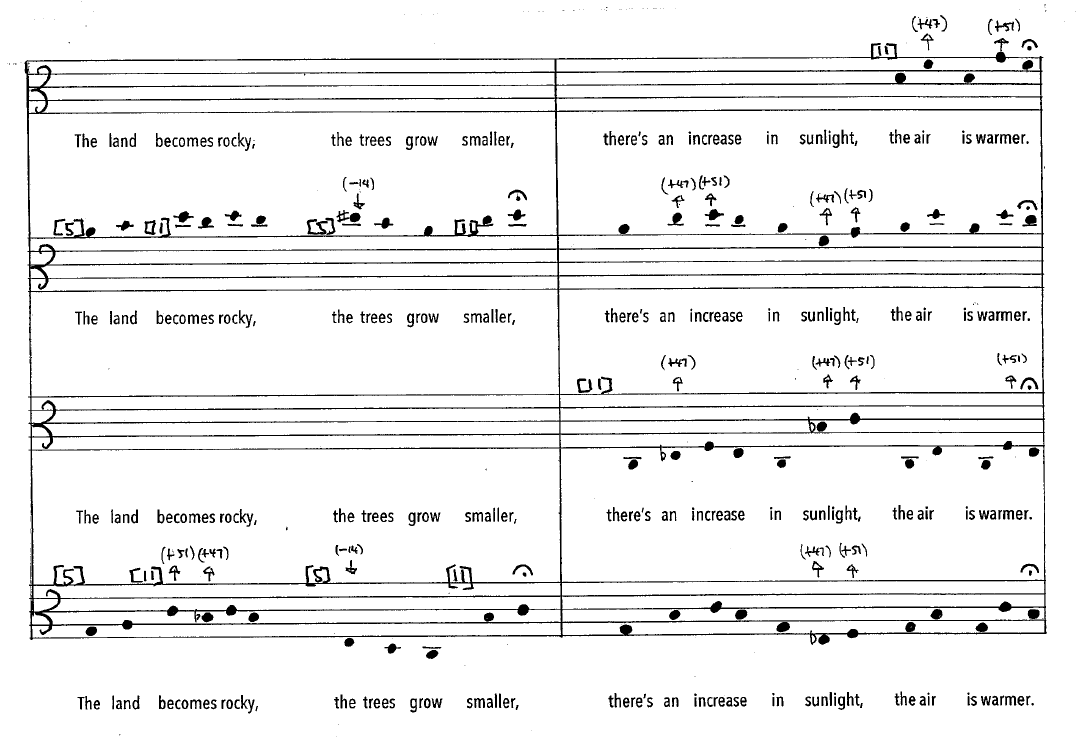

A score excerpt and instructions from Gayle Young’s Departures. Click on the image to zoom in. Copyright Gayle Young.

CB: These pieces have no words, how did you move to writing your own texts, say for your recipe pieces? It seems like a big shift in your practice.

GY: It was! My first concerts in the late 1970s included soprano and alto singers, but the text was traditional, declamatory. I like to think the newer text pieces are more poetic, evocative. My first text-based piece, Along the Periphery, for solo violin, was played by Marc Sabat in a Continuum concert in 1993. It was a shift for me on a couple of levels: paying attention to the sound of the text as I wrote it was very important, as was the meaning, but neither was audible to the listener. Instead Marc played the rhythms and emulated the acoustic textures as he heard them in his aural imagination, also influenced by the mood established in the text.

An excerpt from Gayle Young’s Along the Periphery. Copyright Gayle Young.

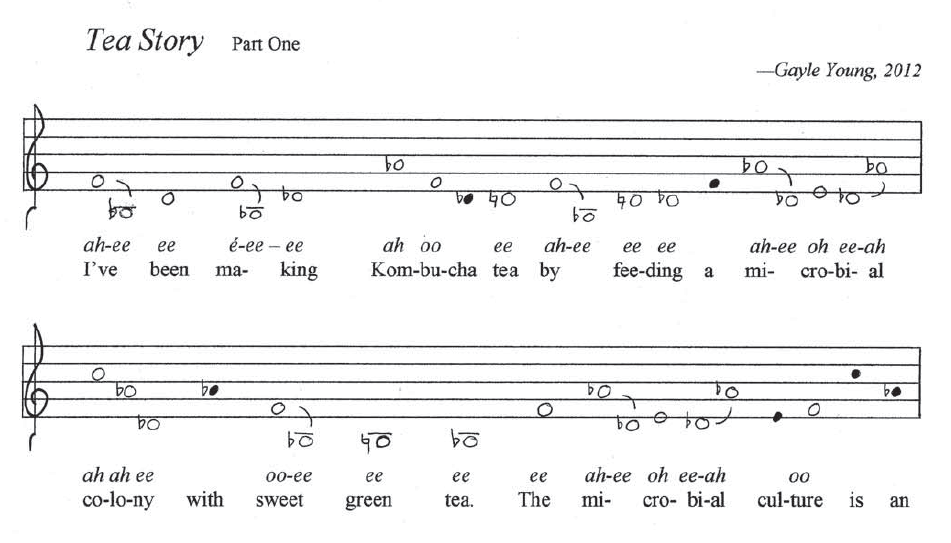

By the mid-1990s I was busy with a lot of non-composing projects and it seemed my music was shoved off into a corner where it wasn’t given that much attention. So I decided to bring the music into the wider world I was living in, by including texts in my pieces. In 1994 I decided to integrate food preparation into the music, and wrote Black Bean Soup, for 12-tone tuning combined with 19-tone tuning. It was played by Marc on violin and John Gzowski on his 19-tone guitar in a Critical Band concert. The text is a description of how to make John’s favourite soup. I’ve written quite a few recipe pieces since then, as well as pieces with texts not related to cooking such as Departures.

An excerpt from Gayle Young’s Tea Story Part One. Copyright Gayle Young.

CB: How does the text work for the listeners?

GY: My intention is that the text-based notations allow musicians to concentrate on the world of sound and listening and aural imagination. Not distracted by sorting out detailed visual symbols. It’s a way to permit a high level of complexity without the anxiety about making mistakes with complex notations. It has taken me a while to articulate the audience part of it, though. In 2014 I was on a wonderful six-week residency with Civitella Ranieri in Italy that I shared with four writers, as well as composers and visual artists. We had sustained discussions over dinner about the role of the text, and I played some of my recipe pieces for them on piano. The basic question was: should I let the audience know what the text is? My tendency was not to, because when I’m in a concert of a piece with voice and the text is in the programme, I can’t listen and read the program at the same time. The text distracts me from listening. Should I read it out ahead of time?

We talked about that, but people aren’t going to remember the details. I was eager to know how the writers thought about this – people who do readings of their poetry so they know about the aurality of text. We kind of decided to describe it this way: I’m writing a letter to the performer, each of those texts is a personal description of, let’s say, the wildflowers that grow in a particular place. The performer translates the letter into sound, and then the audience hears only the sound. There’s always curiosity about what the texts are about though…

CB: I guess that makes the title really important since that’s all the audience sees. How did you go about titling these pieces?

GY: It’s like the title of a poem in a way, but also factual, especially with the recipe pieces, with titles like Buckwheat, Mee-zoh, Tea Story. Others have titles like As Trees Grow, Forest Ephemerals, Ice Creek.

CB: Are you working on any new text pieces now?

GY: I’m finishing Ice Creek for pianist Xenia Pestova, it will be premiered by New Works Calgary in 2018. I’m taking a new step in this piece, integrating the piano part, guided by a text, with pre-recorded audio made through the tuned resonators we talked about earlier.

Gayle will be involved in various activities in the near future. She will be performing at the CMC in Toronto on November 21st which will include a new piece that she completed at a residency in Mexico in 2019. Gayle is also collaborating with composer-performer Amy Brandon on a microtonal augmented reality piece that will be presented at the Winnipeg New Music Festival in 2020.

Xenia Pestova will be performing Gayle’s piano works in Toronto, Montreal and the Newfoundland Sound symposium in June/July 2020, and making a recording at Grant Avenue Studio in Hamilton.