CMC Ontario Regional Director Joseph Glaser sat down with Coreen Morsink, a participant in the latest edition of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Explore the Score program to discuss her participation in the reading session.

Since 2012, the TSO has given some of Canada’s top emerging composers an opportunity to hear their works rehearsed in a live professional orchestral setting. Presented in collaboration with the Canadian Music Centre (CMC), Explore the Score is part of an ongoing commitment to support the development of emerging Canadian composers and the creation of new orchestral works, and to offer the public a front-row seat in witnessing artistic creation first-hand. The program provides some of Canada’s promising composers an opportunity to hear their work performed in a professional orchestral setting and receive mentorship from artistic and administrative staff. The 2022 edition involved advising sessions from the TSO’s orchestral librarian Christopher Reiche-Boucher, RBC affiliate composer Alison Yun-Fei Jiang, TSO’s composer advisor Gary Kulesha, TSO’s music director Gustavo Gimeno, and guest composer Magnus Lindberg.

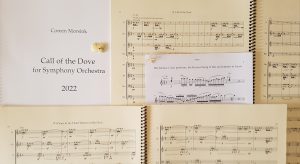

On October 22nd, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra read Coreen’s work Call of the Dove alongside works by Véronique Noël, David Occhipinti, and Patrick Wu conducted by Gary Kulesha.

Joseph Glaser: Tell me a little bit about your background, how did you get into music?

Coreen Morsink: Composing was definitely not something on my mind when I started studying music. I didn’t even really occur to me, particularly as a girl, that I could even become a composer. All the composers I played were men. As a child through to adolescence it seemed perfectly acceptable to become a pianist and piano teacher, which was my first love, but definitely not a composer. Occasionally I’d get optional assignments to write a small piece for theory classes, which I did, but didn’t take that seriously. I was more interested in the direction of piano performance. I went to McGill with the goal of being a concert pianist and teach. In the middle of my university studies, I started writing some folk songs as part of a drama class I was taking. There was a writing assignment in that class and I felt that the easiest way for me to express my ideas was to write songs. I didn’t start really seriously composing until I was thirty years old, after I had my two children. I was working as a lecturer at the University of Indianapolis’s campus in Athens, Greece. My boss then suggested that I get a Master’s Degree in composition as part of a package where I would complete my studies in Composition while also lecturing and promoting their program there. That’s where it started for me. I realized then that I like composing, actually, it made me feel fulfilled. While those compositions, in hindsight, are not masterpieces, I did feel as though they achieved something, and I’ve just gone on from there.

Having started so late, even though I’ve now completed a PhD in Composition, there are still things for which I am an “emerging composer”. For example, through my studies, I never got a chance to write for symphony orchestra, and the Explore the Score program really helped me in that regard.

JG: You did a degree at McGill and have been living in Athens for a while now, do you have a sense of the differences in the composition “scene” in Canada vs. Greece?

CM: It’s a bit hard to say. The majority of my works have been played in England with UK performers since I completed my PhD at Goldsmiths, University of London. The performers I’ve interacted with there are very much into extended techniques using the instruments in very specific interesting and unusual ways. So that has been my “comfort zone”, somewhat strangely! I find since the economic crisis in 2015 in Greece, there has been really no funding for the arts. It’s a real struggle to get work for performing artists and composers, many of them have to tour elsewhere in Europe to make it work. Because of this, a lot of the pieces I’ve written here have not be premiered, outside of the ones I’ve performed myself. I’m still kind of “breaking in” to the Greek contemporary music scene! In the summer of 2020, I realized that I would really like to connect again to the Canadian scene. Fortunately, I was able to participate in CLC/CMC’s PIVOT program with Continuum Contemporary Music in 2021 which helped me get back into the scene in Canada.

JG: Can you tell me a bit about the piece and the intersection between myth and place in the work? How do those elements bear musically on the work?

CM: Since I’ve been living in Greece, I’ve become very interested in ancient Greek music and the mythology behind instruments, ancient Greek musicians and their role in society. One morning in May this year, my husband asked me: “Have you heard the myth about the girl who was turned into a collared dove?” From about May until the end of August, the collared dove is just constantly calling out and it drives you a little crazy. Similar to the cicadas which are also quite irritating and also found their way into this piece. I like my pieces to have stories in them, and I’m also drawn to birds and natural imagery. I hadn’t yet written something about this particular bird, so I decided to go for it. In the story, a girl had to work very hard and felt she was underpaid at only 18 pieces of silver. Her boss said “No! That’s plenty, stop complaining!” and Zeus heard her plea for help and it’s not clear whether he turned her into the bird or created the dove to cry out “Eighteen… eighteen…” or “Δεκαοχτώ [decaochto]” to remind everyone that this girl wasn’t paid enough. Now I’m not trying to say that I’m underpaid! The symphony is definitely not a political or economic statement but it’s amazing that this is from ancient times, around 2500 years ago and they were complaining about wages back then too.

There’s another character in the symphony, the famous musician Linus, who was the “rock star” of his day. When he died, there was a great wailing “ah alas!” which is where we get the word “alas” from. Some mythologies say that there actually wasn’t a person, just a generic term for the harvest, and in the fall when they harvest the flax (linos) they would sing this particular song, the ailinus, which is about the death of fall with the promise of rebirth in the spring and a renewed cycle.

To tie it all together, a couple of years back I had written a very short miniature with a motive around “peace in my heart”. It suddenly occurred to me when I was writing this symphony that that would connect to the dove. Instead of the just representing the dove with this sort of annoying “eighteen” call, it would transform throughout the symphony into a peaceful ending. The call of the dove turns into “peace in my heart”.

JG: How did you approach bringing in literal aural images such as the dove call and inserting them into the musical storytelling narrative?

CM: There are even a few more representations in the piece, the Cicadas are prominent in the second movement, I snuck in a hoopoe bird as well, and a storm that represents the sudden huge rainstorms that happen here. In the beginning of July, we went to a wedding and here, when you’re in the wedding party on the drive to the church, everyone is honking their car horns to celebrate. This piece, with all these sonic elements in it, represents a kind of soundscape of what my daily life was like during the time I was writing it.

More technically, I use remnants of ancient Greek music based on tetrachords and the arrangement of tones, semi-tones, and microtones within the perfect fourth. This was part of ancient Greek music theory, and it’s actually quite complicated all the different combinations (which they called “shades”).

JG: Describe the reading session from your perspective.

CM: The library session was extremely important, finding out some of the problems I had in my parts and score that I hadn’t realized. Some of the things [TSO Librarian] Chris [Reiche Boucher] said about making the score easier to read seemed so obvious but were things I hadn’t considered. It got me thinking about scores I’d sent in the past for competitions and realizing that my scores probably were missing these extra professional touches that I learned from the session. It was a real eye opener.

The actual session at Roy Thomson Hall was amazing, really a dream come true. I was quite nervous to get on stage and actually say something about my piece because as a teenager I would go to TSO concerts as often as possible. If I didn’t have class first thing in the morning I would go down and grab rush tickets and then rush back to class before going back out to the concert in the evening with my friends. I didn’t really believe that it was true that the Toronto Symphony would play my music until I was sitting there listening to it happen. [TSO Composer Advisor] Gary Kulesha was great as well with his insightful commentary during the rehearsal. I particularly liked his comment before the last movement where he told the orchestra to think of it as a giant sigh. I hadn’t exactly thought of the movement in those terms before, but he was dead on. Now I can even put that into the score!

It’s very difficult to square away what you hear in your mind and the midi mock up from the notation software and the actual live experience. I had notated my piece too slow and it made a world of difference with live performers to take the tempo a bit faster at Gary’s suggestion. The orchestra was much more comfortable and I was happy for the suggestion.

JG: Do you have any takeaways from the experience? Now that you’ve heard the work, what are some things you would approach differently for the next piece you write for orchestra?

CM: There was one comment that was made for [Explore the Score participant] Véronique [Noël] about how she used the trumpets with one muted and another not muted to create a kind of hybrid sound. That got me thinking about how, given the number of players in the orchestra, one can create many different sounds without difficulty. In contrast, I asked the flutes and clarinets to make key clicks and, for soloist especially right next to a microphone, that’s a fine technique but the flautist who was at the commentary session afterwards very kindly reminded me that flautists spend a lot of time and money to not make sounds with their keys and they don’t really appreciate it that they are now asked to make all these loud sounds. It’s definitely a different situation writing for this kind of orchestra than for a soloist who specializes in making funny clickey sounds. So, now, if I can find more reasonable ways to make the sounds I’m thinking of, then I will do that.

Overall, I’m very glad I made the effort to come out to Toronto for the reading – it seemed like a once in a lifetime experience and the experience was definitely worth the effort!