CMC Ontario Regional Director Joseph Glaser sat down with the participants in the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra’s reading sessions, Andrew James Clark, Sophie Dupuis, Nathalee Jacques, and Paul Alexander Lessard to discuss their participation in the reading sessions on June 23rd and 25th conducted by Gary Kulesha. Sophie and Nathalee’s readings were the culmination of their tenure as recipients of the HPO Future Award.

Joseph Glaser: Tell me a bit about yourselves: where are you from, where are you located? What is your relationship to classical/orchestral music? What are some current projects you are working on?

Sophie Dupuis: I’m from Edmundston, New Brunswick, and just moved back recently after having spent 11 years in Ontario! I had a pretty traditional relationship to classical orchestral music, though in my own music I try to create imagery and shapes as opposed to working with melodies, for instance. Currently, I’m working on some new works for the PhoeNX Ensemble for dizi, pipa, cello and harp, for Esprit Orchestra and for Ventus Machina, a wind quintet.

Sophie Dupuis: I’m from Edmundston, New Brunswick, and just moved back recently after having spent 11 years in Ontario! I had a pretty traditional relationship to classical orchestral music, though in my own music I try to create imagery and shapes as opposed to working with melodies, for instance. Currently, I’m working on some new works for the PhoeNX Ensemble for dizi, pipa, cello and harp, for Esprit Orchestra and for Ventus Machina, a wind quintet.

Andrew James Clark: I’m just starting my DMA at the University of Toronto in Composition, where I also did my Undergraduate and Master’s degree, though I’ve just taken five years off. I was working full-time as a classroom teacher at a school in Scarborough. Over the pandemic, that school shut down, and while I lost that job, I started an online music tutoring school. Orchestral music is very important to me, because it was my gateway to Classical music. As a kid, I never listened to solo piano music or chamber music, I was always listening to the big orchestra pieces, and that’s what motivated me to study classical music in university. At the time I didn’t realize that we were living in Canada and that our orchestral community is quite small. With that being said, the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra program has been one of the coolest experiences of my life. When I was a naïve teenager going to university for the first time, I was imagining that I would get something like what the HPO is providing for the fellows. After the two years of my masters, I got a little drained, and this program has really reinvigorated me and was part of my motivation to return to my studies.

Nathalee Jacques: I’m based in Ottawa and I did my BA and MMus both at the University of Ottawa. My relationship with classical music didn’t really start until I entered university. I played in bands and sang in choirs in high school, but I always was more involved with the marching band, starting with the cadet program, and now continuing as a cadet instructor. As a result, I was always interested in military music and I didn’t start composition until the end of my BA when I took a composition class for fun. The first piece I wrote as part of that class was a march for Canada’s Sesquicentennial and heard it performed later that summer. It was that experience that made me think “oh this is cool! I like composing and hearing my works played.” As a result, in my masters, I focused on composition but only got the chance to write for small ensembles until this program. In the piece I brought in my background in military music to tie in all the elements of my musical journey. The reading was really great and definitely inspired me to write more orchestral music. It’s powerful to hear a large ensemble playing your work in a different way from a small ensemble. I’m really grateful to the HPO for this opportunity.

Paul Aleander Lessard: I’m actually originally from the States and did two degrees in saxophone performance, at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania and University of Florida, I’m now finishing up my doctorate in music composition at the University of Toronto. My arrival into composition comes at the end of a bit of a tortuous path through music performance. When I was playing in my high school’s concert bands as a saxophonist, I was keenly aware that none of the composers we were playing knew how to properly write for the saxophone. All the pieces had these uninteresting saxophone parts that sat on out-of-tune notes on the instrument. Because I was so unimpressed with my parts, I started re-writing them to give them countermelodies, and that was my way in to composition. For a long time, it was this thing that I did on the side, and finally for my doctorate, I decided that I was going to pursue it full time. Because I had this background with concert band music, I always thought that I wanted to write for concert band. I also had relatively easy access to those ensembles because I would always be playing in them as well. I would go up to the director with a completed piece and say “hey, here’s a piece I wrote, can we perform it?” Because I’m a saxophonist, I never really had that opportunity with orchestra. However, when you’re studying composition, you’re often asked to write sketches for orchestra, especially if you have a teacher involved in that world, like my teacher [CMC Associate Composer] Gary Kulesha, but I didn’t really have the opportunity to engage with orchestras more holistically like that. What was so great about this HPO opportunity is that the orchestra itself was able to give me feedback, not just my composition teacher.

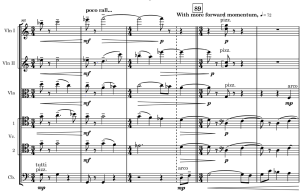

Excerpt from Paul Alexander Lessard’s Légende

JG: Please describe the reading process from your perspective.

PAL: I was asked to write this piece in fall of 2019 and I had had a couple of reading sessions with Abigail Richardson-Schulte about it which were essentially composition lessons, but also a lot of lessons on how to format this thing I was writing so that it’s good for the orchestra. There are certain standards that orchestral players have, they’re expecting to see certain things laid out in specific ways so they can turn their pages properly, for example, and if you as a composer aren’t prepared for that, then it could lead to a bad rehearsal. So, I got a lot of good typesetting feedback from Abigail about that. On the day of the reading, it was very cut and dry: you show up, they play your piece, the conductor turns around and asks you if there’s anything you want done differently, you shout back what you think needs to be different, the conductor rehearses those spots, and in my case, they had enough time to run it a second time, and then away I went.

PAL: I was asked to write this piece in fall of 2019 and I had had a couple of reading sessions with Abigail Richardson-Schulte about it which were essentially composition lessons, but also a lot of lessons on how to format this thing I was writing so that it’s good for the orchestra. There are certain standards that orchestral players have, they’re expecting to see certain things laid out in specific ways so they can turn their pages properly, for example, and if you as a composer aren’t prepared for that, then it could lead to a bad rehearsal. So, I got a lot of good typesetting feedback from Abigail about that. On the day of the reading, it was very cut and dry: you show up, they play your piece, the conductor turns around and asks you if there’s anything you want done differently, you shout back what you think needs to be different, the conductor rehearses those spots, and in my case, they had enough time to run it a second time, and then away I went.

NJ: While I was working on this piece, I was also working on my master’s and studying with [CMC Associate Composer] Kelly-Marie Murphy, so I was able to construct the piece with a lot of her advice as well as Abigail’s. We learned not just about writing for the orchestra but also about the business side. We had some of the HPO admin and librarians give us an overview of the session, how to create the piece, what to include and where. Those sessions were very helpful as well as getting the feedback from the librarian once the piece was submitted – having to make some of the smallest edits that maybe wouldn’t stand out as an error at first but would help things run smoothly. When it came time for the reading, because I had had all this advice from Kelly-Marie, Abigail, and the HPO administration, it went relatively smoothly for the first run-through and a solid second run-through as well. The whole process from start to finish was very interesting and it was pretty neat to see it all come together at the end.

SD: In the reading I realized that 15 minutes goes by VERY fast, but it was pretty amazing what the musicians and conductor, Gary Kulesha, managed to do within that time. They started with a run-through that went pretty well, then Gary did some focused work with the orchestra in certain parts of the piece. I could hear things taking shape and the musicians really getting into it, which was pretty fun to experience.

Hearing my piece for the first time was a little shocking though: it wasn’t quite what I expected and I couldn’t decide if it was successful or not! It wasn’t an unfamiliar feeling as I often do feel insecure about what I wrote when I hear my works live for the first time, but I kind of get over that feeling the more I hear the music in rehearsals, concerts, etc. As we didn’t have the opportunity to hear our works several times, I’m so eager to hear the archival recording with this sort of detachment! But I did receive some positive feedback, so that’s always encouraging.

As the program was also focused on learning about the orchestras behind the scenes, it was great seeing the whole team involved and all the different roles. It helped demystify this “machine,” plus HPO’s team was so kind and willing to share their work! I definitely have a better appreciation of this aspect of the work.

AJC: I was actually slotted in to the reading at the last minute due to an absence. I had done the HPO fellowship this past year and was writing a new orchestral work after Covid hit and I had lost my job as a teacher. I found myself with nothing to do and because I like doing the opposite of everyone else, I thought to myself “everyone is writing these Zoom pieces, so why don’t I write a piece for orchestra?” By chance, I had a lesson with Abigail where I showed her the piece I had been working on, and she invited me to replace the composer who couldn’t be there. With that being said, the piece I was writing wasn’t designed for a reading session, it’s gigantic! Because of this I had to reduce the orchestration and shorten the length a bit. It ended up still being a little too big for what we were trying to accomplish, so my experience was more for my edification than to get a complete piece at the end. I worked with [Conductor] Gary Kulesha to figure out ways in which we could hear all the elements in the score even if we had to reduce the tempo. With those parameters, the piece ended up being very long, and I only got one read through. That being said, I had this gigantic piece that came at the end of a 3-hour new music rehearsal and I couldn’t believe how professional the orchestra was. Despite having site-read new pieces all day, they played it wonderfully and still had the energy to check passages with me after the reading.

JG: What lessons did you learn from this experience?

NJ: My biggest takeaway is that I should come into the experience knowing what I’m there for. I went to the reading super nervous, not knowing how it would turn out. During part of the reading, I even remember literally shaking in the front row just because I was so nervous. I think, however, having the confidence to effectively answer when the conductor asks what could be different. Because I was so nervous this time, I immediately answered “no” because I didn’t want to talk. Not to say the experience wasn’t welcoming and professional at all, I was just nervous about being in the position of authority as the composer. If I was to do something like this ever again, I would like to go in more confidently, take notes on what I want to say and not being afraid to speak up.

NJ: My biggest takeaway is that I should come into the experience knowing what I’m there for. I went to the reading super nervous, not knowing how it would turn out. During part of the reading, I even remember literally shaking in the front row just because I was so nervous. I think, however, having the confidence to effectively answer when the conductor asks what could be different. Because I was so nervous this time, I immediately answered “no” because I didn’t want to talk. Not to say the experience wasn’t welcoming and professional at all, I was just nervous about being in the position of authority as the composer. If I was to do something like this ever again, I would like to go in more confidently, take notes on what I want to say and not being afraid to speak up.

AJC: I learned a similar lesson as Nathalee, I’m so paranoid when I work with large ensembles that someone will be missing a bar, or the parts won’t line up. Because of that, when the reading was happening, I wasn’t listening, I was just praying that all the parts line up. Then when it does work, I’m just relieved that I did my job properly, but then I didn’t actually take in the music. I think, after getting a few readings under our belts, we, as young composers, can go into the rehearsal more relaxed and trust that we proofread our parts properly then we can actually listen to what we wrote.

PAL: I learned that it’s really important that your musical vision is incredibly clear in the piece you write. I’ve heard pieces that are really texturally dense and complex, and in the context of a 15-minute reading, there’s not enough time to pick apart those textures and make them speak. It solidified for me that it really helps if the players are able to situate themselves within the music and know exactly what it’s about thematically and stylistically. It should be really clear right from the music so as soon as the players start playing, they can feel confident that they know what’s going on. Having that clarity is really important when you’re working on such small timelines.

SD: I learned that it’s very important to be incredibly diligent with notes to the performers: some of the musicians understood one of my instructions to be something different from what I had intended. Thankfully, they took the time to reach out to Abigail prior to the reading and ask for precisions, which saved some time during the reading!

I also learned not to be afraid to use louder dynamics!

Additionally, the benefit of having a composer affiliated with an orchestra became quite clear to me. The HPO has exemplary diversity and representation of Canadian composers in their programming. It has this wonderful mentorship program for early-career composers, plus it makes tremendous efforts to do community outreach. These are things that Abigail contributes to in her work with the orchestra and that the HPO is eager to support. As an early-career composer myself, seeing these kinds of collaborations with composers and the doors that it opens for others gives me hope.

JG: Is there any responses you have to what your colleagues have talked about?

PAL: Nathalee touched on it a few questions back, but when you’re having these readings, there’s a lot more to this program than this. We also got to learn from the orchestra administration, for example, the personnel manager told me “This is why you can’t have a saxophone all the time Paul!” We also got to talk with [HPO Music Director] Gemma New who told us how to strategize the instrumentations that would hit the right receptors for the most orchestras. We all like to dream of writing for the full orchestra with triple winds and 4-3-3-1 brass but most orchestras are looking to program for a smaller orchestra with double winds and two horns and maybe a trumpet. Meeting those smaller personnel needs gives your piece more of a chance to be performed. Similarly, she mentioned how it can be a good idea to use the same instrumentation as a smaller-sized but well-known work, like [Prokofiev’s] Peter and the Wolf so then it would be easier to program your piece alongside it. Getting that view into how orchestras make decisions and how they are run is really helpful when trying to enter into that world.

AJC: Abigail was very generous with us and gave each of us all the scores for the entire rehearsal, and it occurred to me (2 days later after my brain had enough time to process everything) that every time Gary had to stop the rehearsal it was because of some sort of non-specified rhythmic music symbol. In one piece it was a fermata, in another there was a breath mark, in a third there was an arhythmic Canada Goose call, even a grace note figure in another piece halted the rehearsal. When I was thinking about it, I realized that about a half an hour overall of the rehearsal time for the day was taken up specifying these little rhythmic symbols. I was wondering why that is, and I remembered that so many composers are pianists and a fermata, grace note, or breath marks are no big deal for a pianist, but with the whole orchestra it became an issue. That’s something I could never have learned in university! Now I’ll never not be super specific with rhythmic elements like that.

AJC: Abigail was very generous with us and gave each of us all the scores for the entire rehearsal, and it occurred to me (2 days later after my brain had enough time to process everything) that every time Gary had to stop the rehearsal it was because of some sort of non-specified rhythmic music symbol. In one piece it was a fermata, in another there was a breath mark, in a third there was an arhythmic Canada Goose call, even a grace note figure in another piece halted the rehearsal. When I was thinking about it, I realized that about a half an hour overall of the rehearsal time for the day was taken up specifying these little rhythmic symbols. I was wondering why that is, and I remembered that so many composers are pianists and a fermata, grace note, or breath marks are no big deal for a pianist, but with the whole orchestra it became an issue. That’s something I could never have learned in university! Now I’ll never not be super specific with rhythmic elements like that.

NJ: I think one of the greatest things about the program is that we were invited to a lot of rehearsals and I think that there are so many valuable lessons to be learned just by sitting in on rehearsals and following along. There are a lot of things in that scenario that you’ll experience differently than if you were to just, say, go to the concert. When you’re listening to a professional orchestra, they make it sound easy, but when you sit in on the rehearsals you can pick up on the elements that end up requiring more time. Some of those elements you wouldn’t even imagine would be problematic until you attend the rehearsal. I very much appreciated being able to take in those rehearsals.

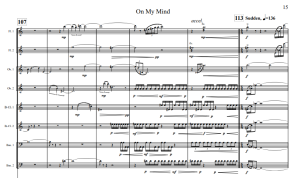

Excerpt from Nathalee Jacques’ On My Mind

SD: It sounds to me like the program was a great practice run for everyone to try new things and work with an orchestra ahead of being situated in a “real-life” professional context. We were provided with the proper tools to take the most out of the experience, and then we were given the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them in a safe environment. This ensured that each of us could gain a new set of skills that was both timely and meaningful to us and for our own path, even though we were all early-career composers with different backgrounds and interests.