Focus: Audio Quality and Livestreaming

By Pouya Hamidi & Matthew Fava

Contents

Introduction

As we are writing this post we are entering the second month of quarantine and confronting projections that large gatherings for live music may not return for some time—an ominous scenario for our communities. The sudden and necessary prevalence of live-streamed performances takes on greater significance as we imagine a near future of connecting with remote audiences.

Given the conditions of isolation, there is an expectation during current live-streamed performances that the artist serve simultaneously as technician and performer. At the same time, the audience members experiencing a wider selection of live performances quickly realize that the myriad solutions for live-streaming (and the equipment or applications that are readily available) do not guarantee the best quality of audio.

When the CMC began implementing live-stream infrastructure several years ago, we connected with the co-author for this post, Pouya Hamidi. Pouya is a Toronto-based composer, musician, and audio engineer, and he has been a recurring presence in our Toronto venue for live and recorded sound. He is also the person we consult with when costing equipment and software for live audio. Pouya, like many great audio engineers, blends artistic and technical sensitivities.

In the last month we have gotten a lot (a lot) of inquiries about livestreaming, so we figured this post would be a helpful resource for artists planning solo livestream performances from home—many of the principles can also apply to more ambitious programming in future when ensembles/bands can gather together. Below you will find several headings as we outline the steps and costs that help us improve audio quality, minimize troubleshooting at the point that we go live, and make the experience for audiences/communities that much greater.

We’ve simplified this guide, but encourage you to reach out with feedback, or questions.

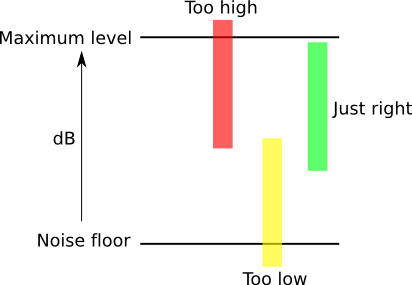

Let’s Review Some Basics

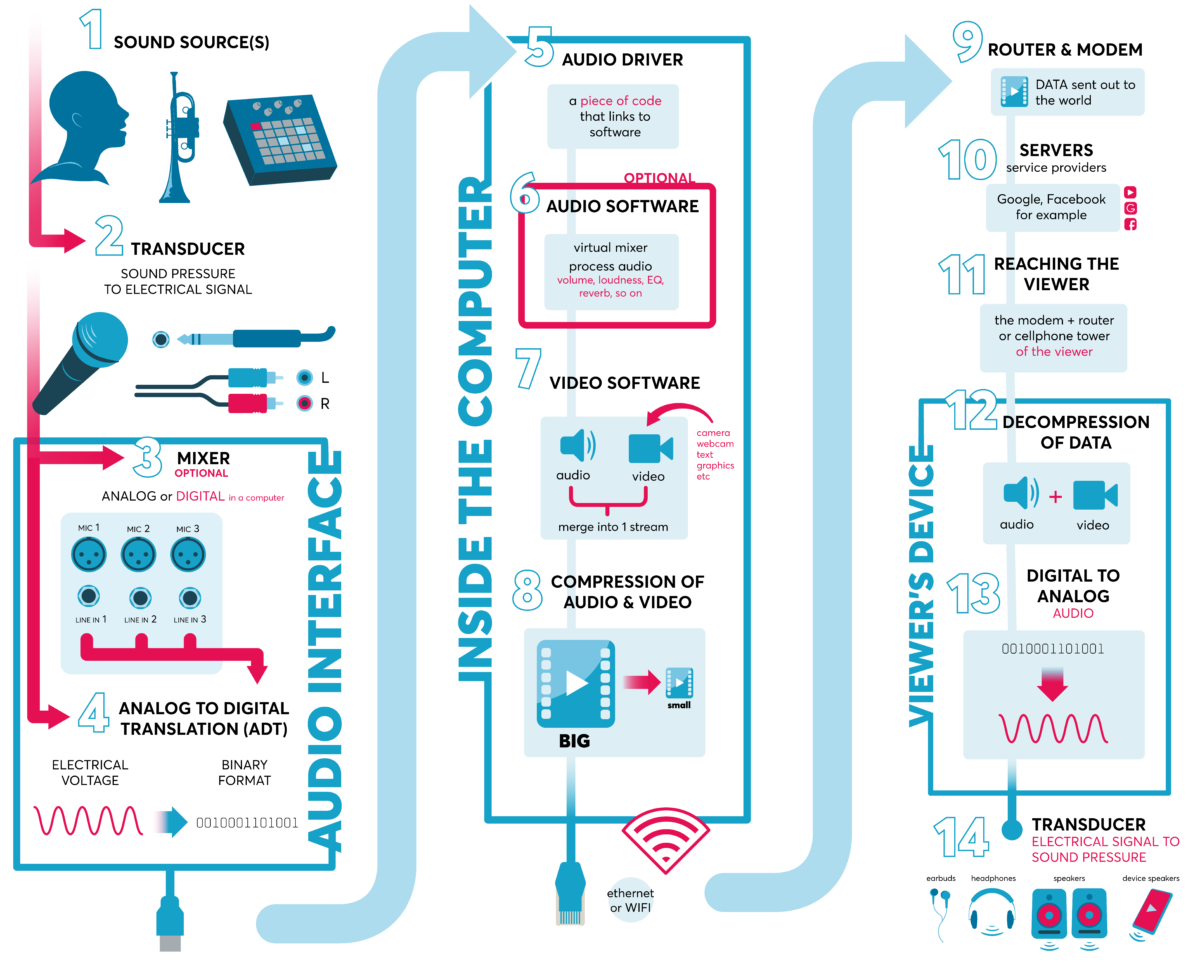

In order to improve the quality of live streaming audio, it is important to go over the path sound takes from the musician’s instrument to the viewer’s ear. Understanding these steps will not only help guide the musician to generate better audio quality but also help with troubleshooting their systems to identify challenges or make improvements. We have created an illustration (Media 1) and description for each step below. You can click on each number to expand it.

A Practical Guide

Now that we have looked at the various stages of your audio signal when streaming to the world, we thought it might be helpful to go through the different approaches you might consider when setting up your audio at home. We’ll then take one of these approaches and create a hypothetical scenario and walk you through the steps.

Different Approaches

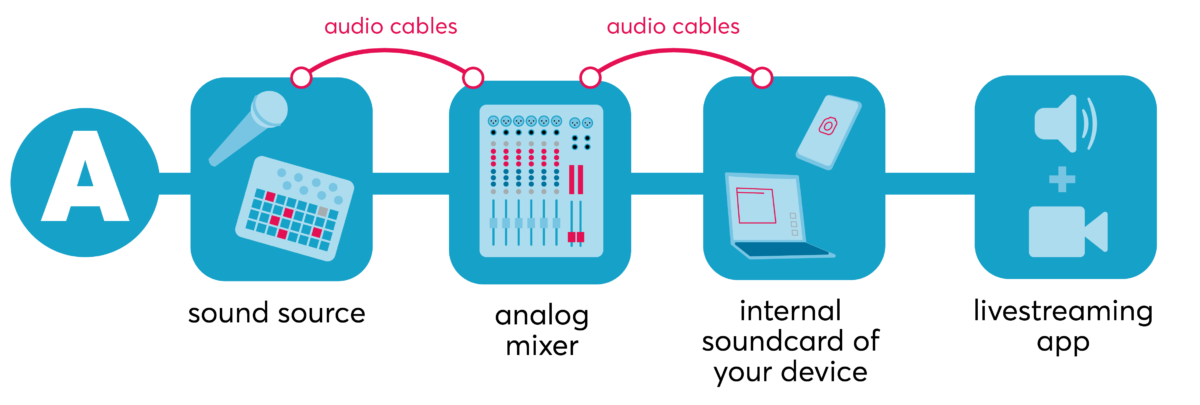

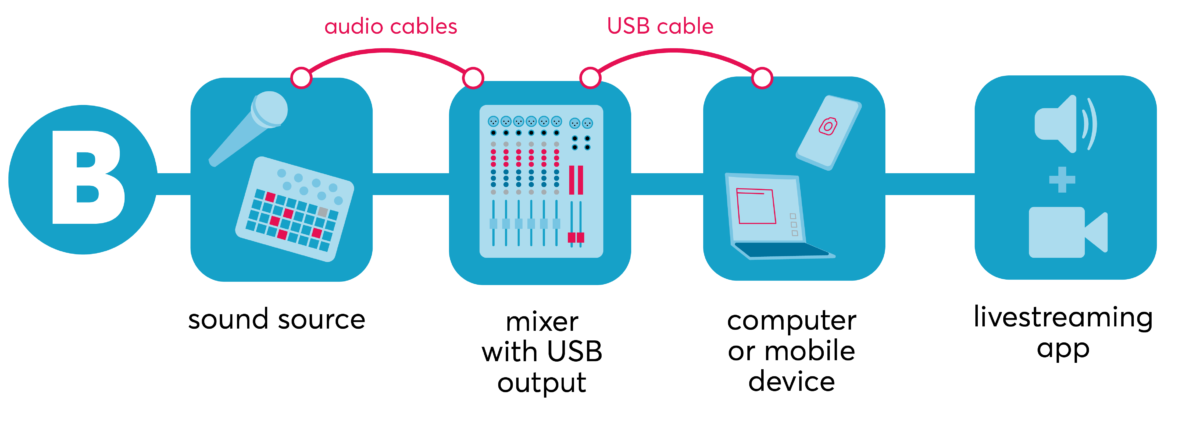

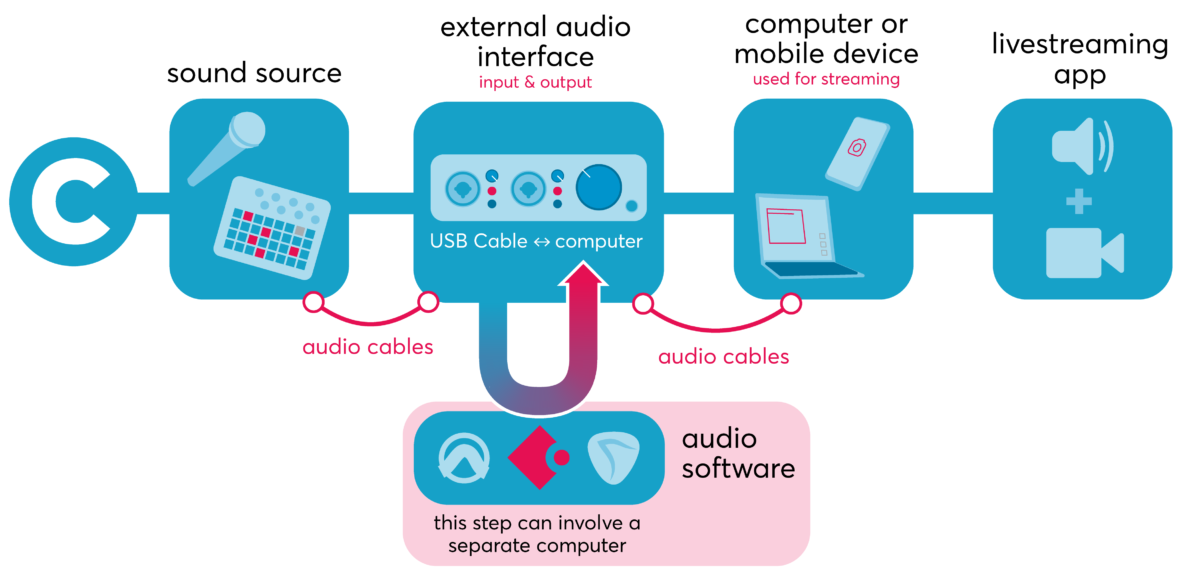

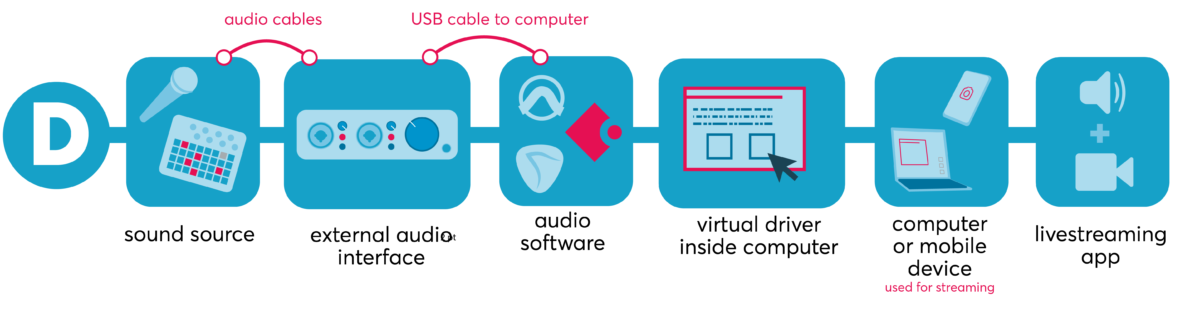

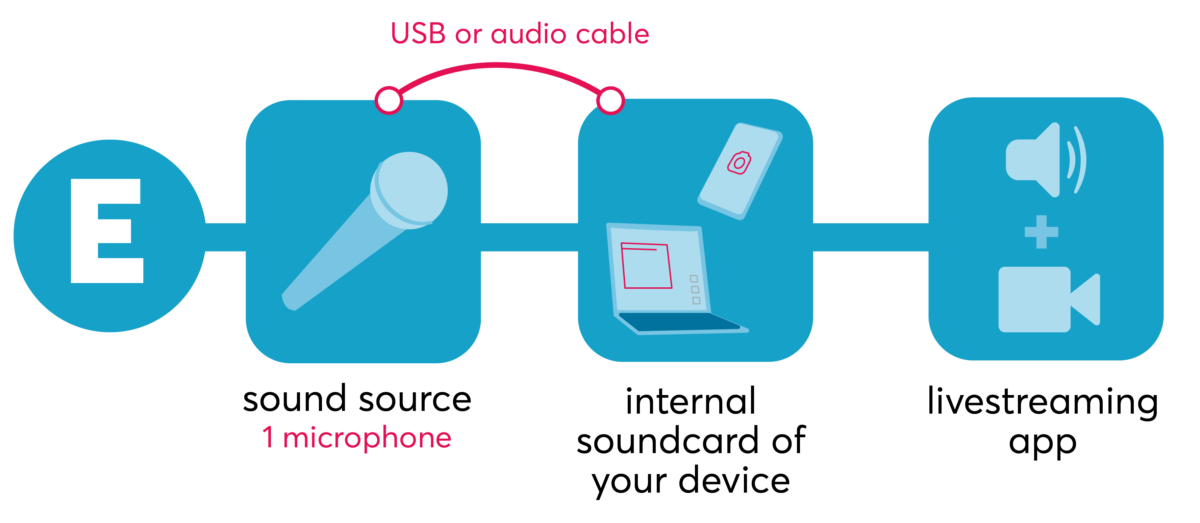

We will explore some options of connecting different audio components together below. You will notice that there are some similarities between some methods.

A quick gear/software disclaimer: we do not favour one manufacturer over the other in this article. We are simply suggesting examples so the reader can familiarize themselves with some options in each method. We also have received multiple requests for equipment and software recommendations, and thus want to anticipate some of your inquiries. Please read online reviews, research, and familiarize yourself with their features/complexities before acquiring them. And as always, look into options for renting or borrowing!

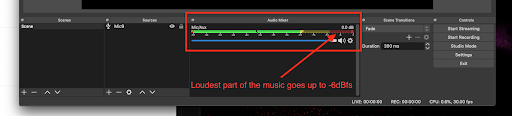

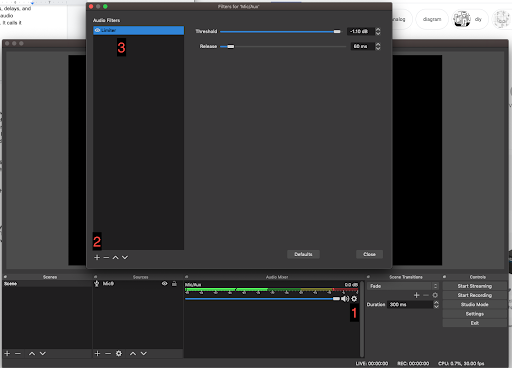

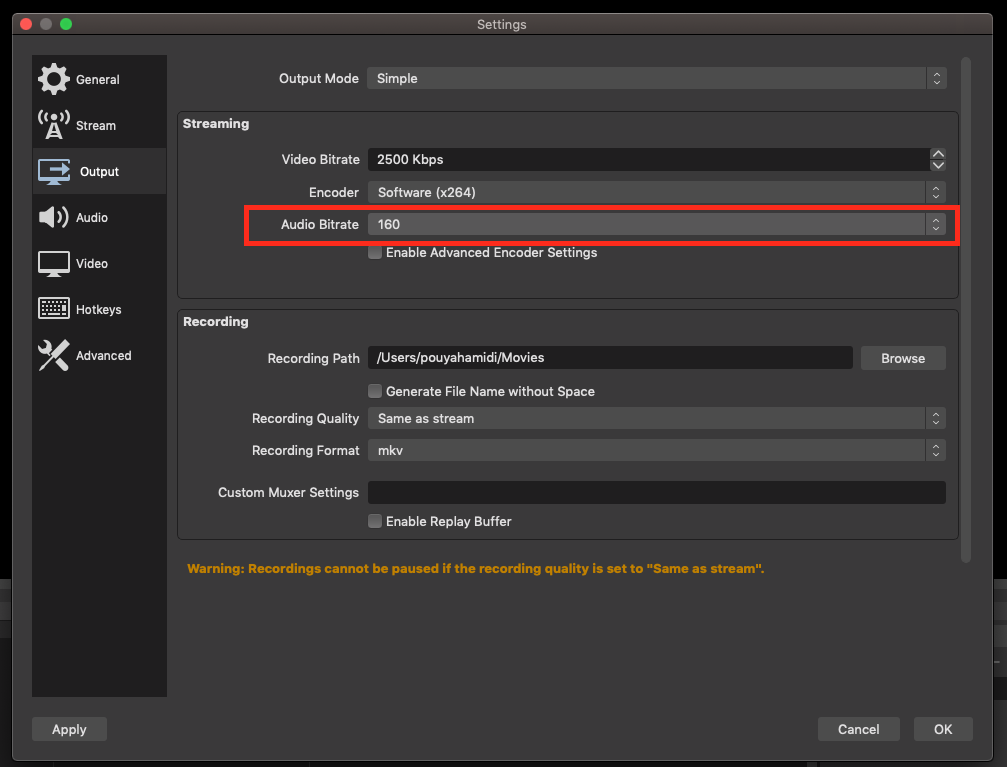

A Step by Step Example

Below we’ll walk you through steps needed to create a higher quality audio setup (relative to using the internal microphones of your computer or portable device) for live streaming.

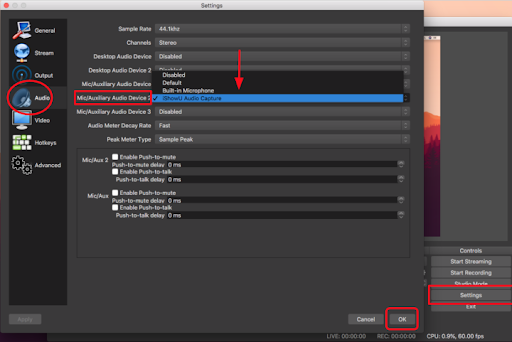

We’ll take a hypothetical example of a musician who plays flute, a synthesizer, and drum machine all at the same time. They are presenting an online concert for their fans. As illustrated above, other approaches are possible but we’ll use Method B. We’ll be using the mixer Zoom L-8 which has a USB connector.

Gear used in this example:

- Cardioid microphone: Audio-Technica AT2020

- Headphone: Audio-Technica ATH-M50

- Mixer: Zoom L-8

- Cables: one microphone XLR cable, multiple TRS cables

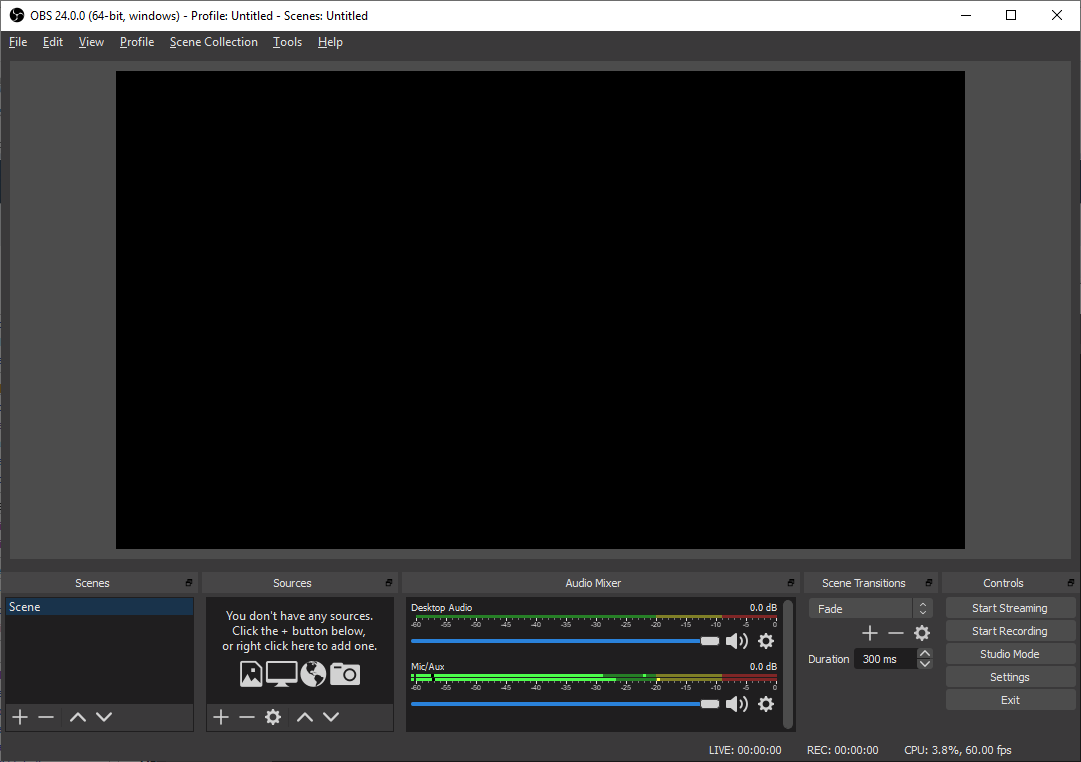

- Live-streaming software: Open Broadcaster Software

Conclusion

We hope that this article has been helpful and that it provides at the very least the groundwork for you to explore this topic further. Audio production and live audio are deep topics and you can devote years to learning and refining your techniques. Audio production can get complicated, but remain patient. We live in truly extraordinary times and there is a wealth of knowledge in our communities and online.

Dig in and try out some of these methods. As we mention, they will require a lot of trial and error and testing.

Thinking more broadly about the world we inhabit and the culture we embody as artists, it is not fair to expect everyone to suddenly master all of these techniques, nor should every artist purchase a lot of equipment (especially when the usual financial model that we depend on for income is dormant and unavailable to us). This is not the expectation. We can find other solutions to help us through the next year as social distancing might allow for small gatherings of collaborating artists and technicians while prohibiting/limiting in-person audiences.

If your livestream is being presented by an organization, indicate some of the technical costs that are required and ask that they compensate you for those added costs. Apart from equipment like microphones and mixers, internet capacity is a major factor. Many of us have wireless/wifi that is insufficient for uploading live video. Tell your presenting organization that you would like to include the cost for upgrading your internet connection as part of your fee in order to ensure a higher quality stream. You can also consider short-term equipment rental from businesses like Long & McQuade, or pay to rent gear from some of your colleagues.

Let’s remember the reasons that we have venues, publicly funded presenters, and festivals. Let’s remember why we have a collaborative model for event production with a division of skills/labour. We want to value and celebrate the various specializations that combine to define a music community. In the same way that we invest in social programs like health, education, and transit, we should look forward to reclaiming and (re)building those collective spaces that foster the art making that we love.

While we adjust to the evolving realities and implications of social distancing, don’t hesitate to reach out and when you have the means, hire the audio engineers in your scene.

Endnotes

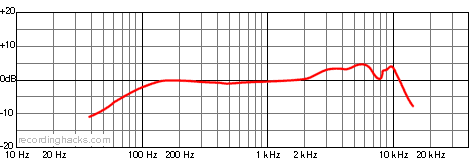

1 “Shure SM58 | RecordingHacks.com.” http://recordinghacks.com/microphones/Shure/SM58. Accessed 16 Apr. 2020.

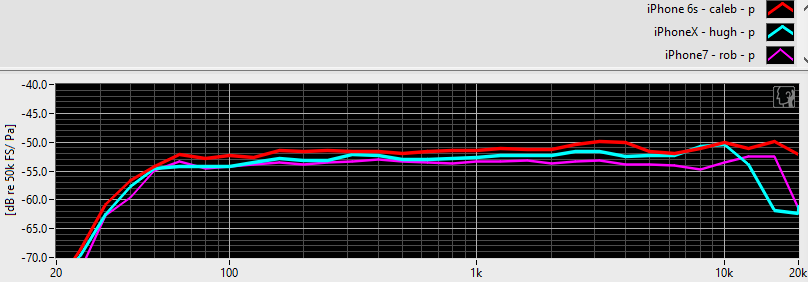

2 “Can You Use an iPhone’s Internal Microphone for Acoustic ….” 22 Mar. 2019, https://signalessence.com/can-you-use-an-iphones-internal-microphone-for-acoustic-testing-and-accurate-recordings/. Accessed 16 Apr. 2020.

3 “4006 Omnidirectional Microphone – DPA Microphones.” https://www.dpamicrophones.com/pencil/4006-omnidirectional-microphone. Accessed 16 Apr. 2020.

4 “Audio recording for live events – Epiphan Video.” https://www.epiphan.com/solutions/audio-recording-for-live-events/. Accessed 17 Apr. 2020.

5 “Open Broadcaster Software – Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_Broadcaster_Software. Accessed 17 Apr. 2020.

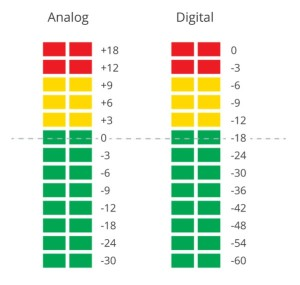

6 “Gain Structure 101 – miniDSP.” https://www.minidsp.com/applications/dsp-basics/gain-structure-101. Accessed 18 Apr. 2020.