By: Juro Kim Feliz

N.B. This article is the third installment of “Nomadic Sound Worlds,” a four-part series that explores Canadian contemporary music through the lens of present-day global migration. Published in 1999, a collection of essays named Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss (ed. André Aciman) informs this project, with trajectories branching out from related themes including mobility, displacement, loss, reconciliation of polarized truths, and invention of selves. In this regard, the series will feature selected immigrant Canadian artists whose worlds collide with various personal stories of immigration.

Venturing towards downtown Toronto with a bicycle from North York has its own pros and cons. Aside from keeping transportation expenses low, physical fitness comes both as a priority and a reward. In one of these bike rides, I stumbled upon Harbourfront Centre on a cloudy June summer day and saw the House of Mirrors bending the perceptions of space and depth for those who enter it. Receiving its North American debut at the 2019 Luminato Festival, I decided to enter it and found myself inside a huge maze of mirrors conceived by Australian artists Christian Wagstaff and Keith Courtney. Acting as a modern-day Minotaur proved to be a challenge, with all surrounding mirrors confusing the senses and blurring the lines between reflections and real passageways. Most importantly, I found the resulting juxtapositions of various images very fascinating—one would see fragmented reflections of tall buildings and the surrounding city skyline. This is definitely what Toronto looks like, I thought to myself.

In the wake of the Toronto Raptors’ NBA championship win that brought the whole nation into a united frenzy, Omer Aziz wrote in the New York Times that it was as if the whole of Canada has found its identity in such victory. Harbouring the story of being the underdog, Toronto now thrives with the majority status of the minorities.1 Turning an eye back to the House of Mirrors, seeing how the angled surfaces distort my view of the CN Tower nearby led me to introspection: people would assume that social cohesion among Canadian communities appears more like a seamless quilt, a “cultural mosaic.” Just like in a Monet impressionist painting, one sees the dynamism of light and colour from afar as much as rugged brush strokes become visible upon close range. To follow that observation, how many of these communities felt more like these awkwardly cut-out pieces of grotesque buildings, all taped and patched together? Moreover, how much of that had to be invented from the ground up, just like how this visiting installation reinvents Toronto as an odd, fictitious patchwork of skyscrapers? As much as diverse accents and attitudes within a city still come off as fiction to many parts of the world, does increasing globalization force different peoples to confront their own constructs about political identities?

To conjure an answer, I asked three Canadian composers to contribute their own stories of mobility and belonging as they invent their own ways of navigating through the zeitgeist embedded within their current circumstances. As it turned out, the gestalt proved greater than the culmination of multiple stories, and the process seemed to open up more questions than satisfying answers about political borders and citizenship to incite belonging.

Being “twice displaced…” or was it “thrice displaced?”

With increasing discontentment among the working classes of China after World War I, the May Fourth Movement in 1919 progressed within a series of massive student protests that clamoured for cultural reformations against imperialism and feudalism. The Communist Party of China emerged with a newfound ideology that embodied the hope of ending oppression from extreme inequality among the Chinese populations and the intrusion of foreign powers. Fighting over survival against the ruling Nationalist Party after a breakdown of relations and a massive purge, the ensuing civil war across the country in the late 1940s finally rendered the Communist Party victorious. This ripped the entire Chinese population, creating a huge exodus of Nationalist supporters as they fled to Taiwan. The competing claim for legitimate sovereignty and governance between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China in Taiwan continues under what is now known as the “One-China Policy.”2

Photo of composer Dorothy Chang

There was no way to evade touching on this tidbit of history upon meeting Vancouver-based composer Dorothy Chang at the Soundstreams Emerging Composers Workshop in Toronto this year. Tracing her roots from an Illinois suburban town, she recounted her parents’ stories as their families were exiled under dramatic circumstances. “My dad’s family made it to Taiwan [from mainland China] when he was 12, and my mother when she was 9,” she told me. “I think both of them never identified with Taiwan even when it became their new home because that’s where they fled to, where they fled their home to.” But was it really that worse at the time? I thought. “My mother had barely escaped as stowaways in a military plane after three days of no food or water,” she continued. “My maternal grandfather was a lieutenant in the Nationalist Air Force stationed in California, and he returned to China to evacuate his family as the Communist army was closing in.” They escaped to the nearest airport and were stuck with thousands of civilians who were waiting for evacuation that never came. Having access to the restricted military area of the airport, he found this plane filled with ammunition and actually didn’t know whether it was going to the frontlines or retreating to Taiwan.

Dorothy continued: “He snuck his family aboard, the plane took off, and didn’t know their fate until they saw water. Apparently they were discovered by the pilot once they were airborne, but my grandfather outranked the pilot.”

Pursuing graduate studies at the University of Illinois in the 1960s, Dorothy’s parents were destined to meet, get romantically involved, and build a family in the United States as immigrants. Not surprisingly, this familial relationship with Taiwan also led Dorothy to spend some of her formative years there. “When I was 13, my family moved to Taiwan and I was there for only 3 years. We were among the expatriate community, where I found my peers which is really this ‘twice displaced’ people of Chinese heritage.” She explained that her peers were born in the United States who came to Taiwan, who were not Taiwanese and also not really Chinese and American at the same time. “We have this hybrid [background]—it’s a very specialized group and I felt, ‘Ah, these are my people!’ I met other individuals with similar kinds of backgrounds, but this [community] was formed from being ‘twice displaced’ foreigners in that land and being foreigners once again coming back, but with one foot on this culture and one foot on another.”

It is interesting to point out that her parents’ exile even trickles down into her own positionality. The question of home becomes a matter of significant contention. “’Homeland’ is odd,” she noted. Despite familial relationships with the island, Taiwan is not the homeland anyone expected them to identify with. “For my parents, China is the homeland. When we were young, we didn’t distinguish between the two because my parents are Chinese. Even though they’re from the Nationalist point of view, China is their homeland.” She joked that maybe she is “three times displaced” after all, but returning to the United States made her realize that the sense of belonging she found in the sheltered, expatriate community will never be recreated again.

“You have to go see this tiny, elderly lady…”

At the other side of the world, the disillusionment from corrupt governance and economic stagnation descended in Cuba during the 1950s as the population experienced increasing income disparity and a widening economic gap between Cuba and the United States. Fulgencio Batista’s rather dramatic return to power via a bloodless coup did little to mitigate the discontentment, and opposition to his regime solidified upon his illegitimate suspension of the electoral process. Fidel Castro’s persistent initiative of armed insurgency eventually evolved into a nationwide revolution that led Batista to flee the island. Purging all opposing parties, Castro consolidated all powers and successfully gained leadership of the whole country.

Vancouver-based composer Sergio Barroso was no stranger to the land. Growing up as a native of Havana, he was intimately immersed with the thriving multiculturalism even within the communities that propelled national arts and culture in the country. During a phone call with him, his enthusiasm abounds in the conversation at hand: “In my teens, my parents used to invite painter friends in the house, and they have original paintings [hanging at home]. We would have Wifredo Lam, René Portocarrero, Fayad Jamís—these famous Cuban painters with artworks exhibited in the National Museum.” Basing on the names of these painters, one would be amazed at Cuba’s syncretism and social diversity apart from Spanish and African roots. He continued to explain: “There is a very intense Chinese culture, an intense Irish culture, a very powerful French culture, different African cultures that came with the Haitian Revolution (the Yoruba and the Abukua from Nigeria, the Bantu from Congo and Angola), and even Jewish, Lebanese and Arab influence. You’ll think that it is a kind of mosaic—they’re all fused and it was very difficult for me to think that these people are different from me. Cuban society is all very compact and integrated, not divided and spread out like here in Canada.”

Photo of composer Sergio Barroso, taken in Bolivia (2014)

Even at a time of intense political upheaval and suppression, Sergio found the arts community at its prime in the 1960s. Like Dorothy, he found immense opportunities and a great sense of achievement within that solidarity—things that can’t be replicated anymore elsewhere.

“There was that euphoria in the country,” Sergio said. “People weren’t interested in doing things for money. Everyone I worked with literally did things for the sake of art. You could basically go and talk to an orchestra, have them for a gig aside from their regular schedule, and have them play for free! Everyone got enthusiastic about doing new things. That decade of the 1960s was really special, but then if you have politicians in power for too long, they can get used to it and refuse to let go. That system is exactly what happened to Cuba—everything gradually started to change, and there were absolutely unacceptable situations in the country by the 1980s. The euphoria was gone—there were lots of protests against the ongoing repression, along with many people who wanted to leave the country.”

True enough, many thousands had already emigrated to the United States during the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution as Fidel Castro pounced on “enemies of the state” early on. Many of these exiles were non-allies and numerous supporters of the previous Batista regime. Throughout this period of fresh political mobilization, Sergio pursued postgraduate studies at the Academy of Performing Arts (Prague), the University of Havana, and Stanford University. As living conditions in Cuba changed with stagnating economic growth over the following decades, a different kind of bureaucracy took over the country. Despite building an international career as a Havana-based composer, Sergio would encounter a complex and stifling form of political suppression.

“When you are in a political system like Canada’s, if they say ‘no’ in this door, you can go to [another] door. You’ll eventually find a door [of opportunity] where you can do [something] with your own resources,” he explained. “In Cuba, there’s only one door. If that door says ‘no,’ you’re stuck.” The year 1980 was a major turning point for Sergio, winning awards at both the UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers in Paris and the Concours International de Musique Électroacoustique de Bourges. “If you’re invited to a festival, you have to go see a tiny, elderly lady working in the Department of External Affairs in the Ministry of Culture. She would decide if you’ll get a passport or not, if the state will pay for your plane ticket or not.” A power struggle ensued at this moment of success for Sergio—the lady firmly told him she “had no time to deal with that.” As a chairperson of the Department of Development in the Ministry of Culture at that time, he had to see the Vice Minister personally and get everything settled top-down. That’s when he realized the severity of the isolated position Cuba was in. “I took my chance. I’m leaving, I’m never coming back,” he concluded.

Personal matters also complicated things for Sergio. His eldest son couldn’t leave Cuba at a young age, especially that Sergio’s ex-wife and her new family had departed the country and left him behind. Signing the authorization as a father for the mother in exile to get him out of Cuba would be suicide, as Sergio would end up being branded as an enemy of the regime. “The only opportunity for me to do that was to stay in France, find a lawyer a few months later, making legal authorization [outside the country] and mail it so that he could leave. I was already out; they couldn’t take reprisals of me.”

Even with the prestige of receiving the awards at Paris and Bourges, what possessions had he brought with him at that time? “The only thing I took with me was a suitcase with my scores and recordings,” Sergio said. “That was it. Fortunately, airport security staff didn’t think of opening it.”

Imagined Cultures and Inventions

In his book Imagined Communities, sociologist Benedict Anderson redefined the concept of nationalism at a time when confidence in such notions were gradually collapsing following the wars and exploitation they bolstered under fervent nationalism throughout the 20th century. What does it mean to love one’s nation when societies engage in conflict? When they reproduce immense inequality? When they regulate the flow of global capital? Anderson wrote that, “[the nation] is an imagined political community—and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.” Four points are vital in this definition: (1) it is imagined (“even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members…yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”); (2) it is limited (“even the largest of them…has finite, if elastic, boundaries, beyond which lie other nations”); (3) it is sovereign (“nations dream of being free, and, if under God, directly so”); and (4) it is a community (“regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation…the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship).

To sustain itself, this imagination relies on the invention of social ideologies that seamlessly weaves historical narratives, the use of language, ways of disseminating information, and even folklore and mythologies into meaningful forms for its constituents. This recognizable, shared understanding renders its existence indisputable, unquestionable, and inevitably ingrained as truth. Anderson highlighted the element of sacrificial love one commits for the nation-state that, “for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings.”

Languages and “jitanjáfora”

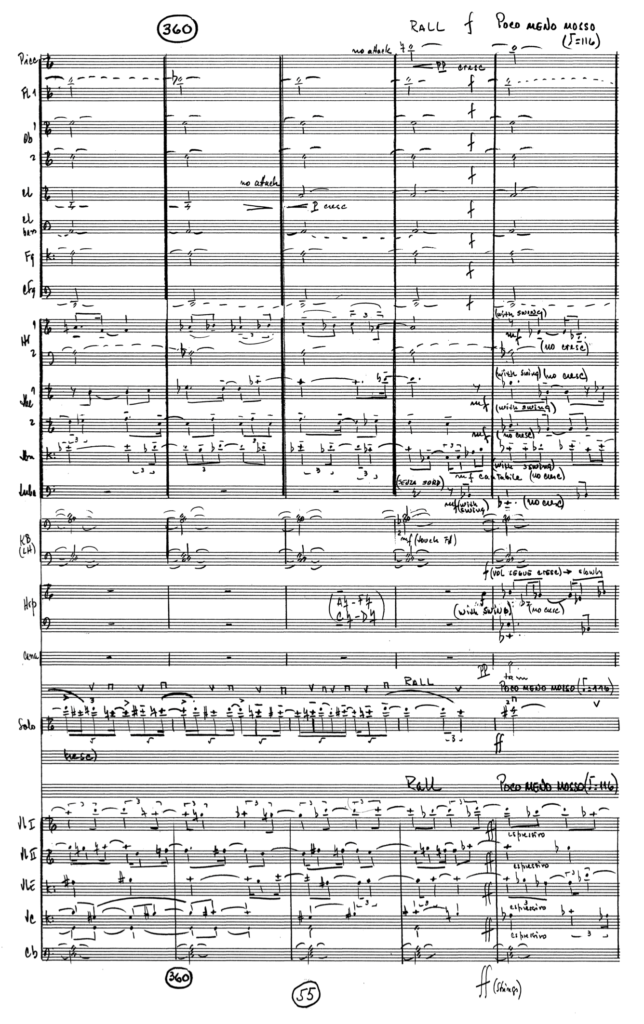

The composer’s creative force hinges on the same spirit of invention, whether it revolves around examining new sounds or simply responds to creating new music for whatever purpose. While Sergio Barroso’s work Jitanjáfora is no exception from such a process, reviews of its performance were unrelenting: “the best piece for the occasion…an anti-concerto…its profligate style and lack of good breeding made a refreshing break from the polite utterances that had preceded it [in the program];”3 “a flamboyant score…the concerto is the kind of piece that pops its cork noisily;”4 “with one of the orchestral sections exploding in the manner of a Latin cabaret band, Jitanjafora may possess more color [sic] than originality, but it certainly sounded thought through.”5 Composed for the Raad electric violin and orchestra, soloist Adele Armin and the Esprit Orchestra premiered the work along with a subsequent broadcast on CBC’s now-defunct music programme Two New Hours. While William Littler opined that the work “[churned] out a succession of musical episodes…but giving very little impression of cohering into an overall entity,” I see Jitanjáfora instead as a witness to Gustav Mahler’s spiritual evocation of humanistic creation in his Eighth Symphony. Keeping the pretext of the hymn “Veni creator spiritus” in mind, the word “jitanjáfora” itself is a created fabrication—the Cuban poet Mariano Brull made up the term to enable word invention within a formal literary structure based on rhythm and sound colour. If made-up words don’t need to mean anything other than disguising itself as a familiar language, then should illogical, episodic structures carry the same expectation?

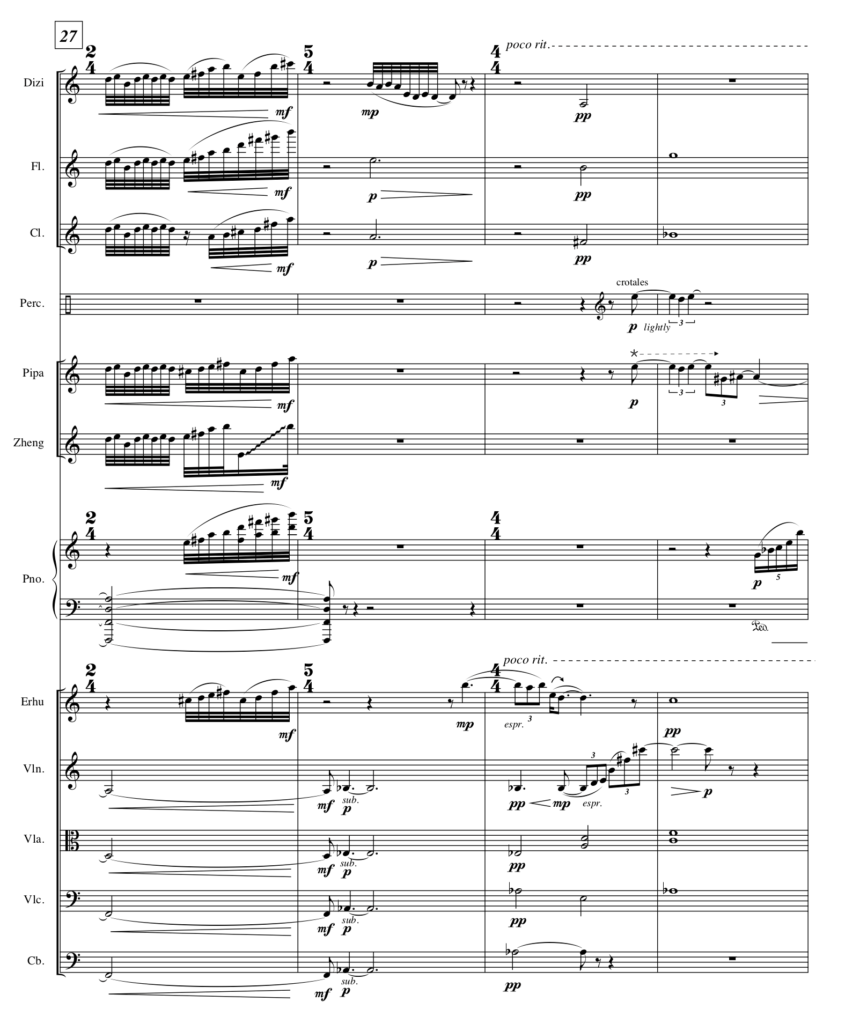

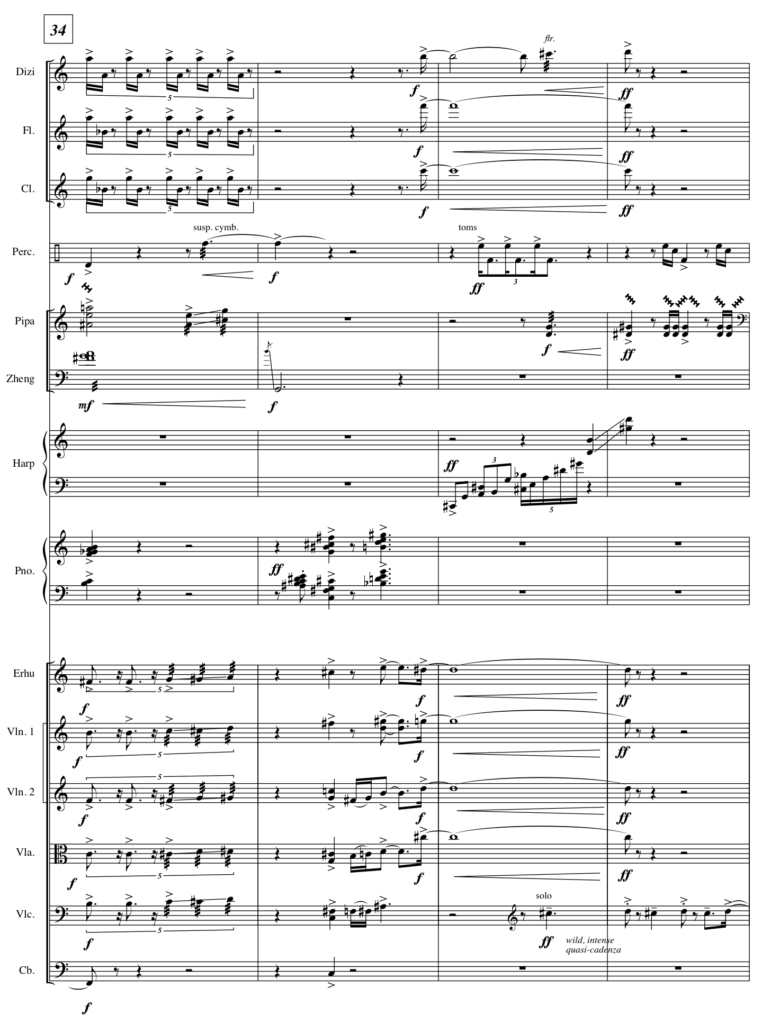

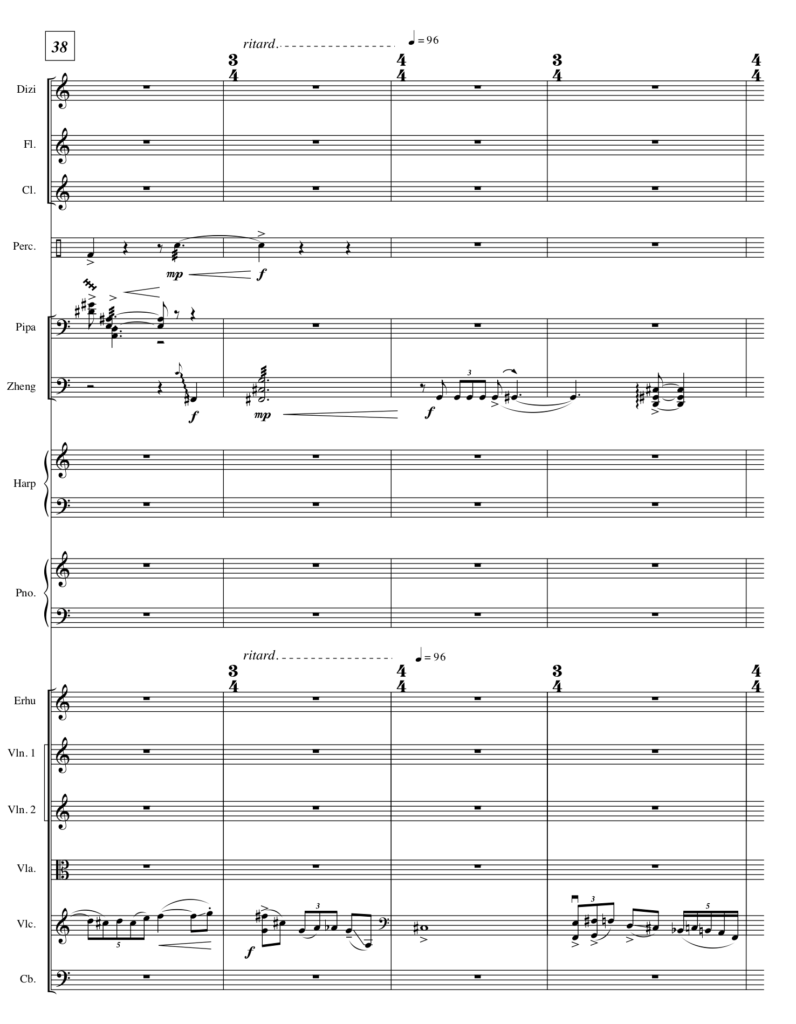

Score excerpts from Jitanjafora (Copyright, Sergio Barroso) A particular ominous moment when Cuban brass music thinly emerges in the soundscape, leading to the climactic ending of Jitanjafora. This is reminiscent of Matthias Spahlinger’s ghostly homage of Guillaume Dufay with “Adieu m’amour.” Click to expand the view of the score images.

But what struck me is that the CBC broadcast, along with William Littler’s concert review (“Esprit Orchestra season opens with Canadiana”), rendered Jitanjafora into an icon—it’s now seen as a piece of Canada, a symbol of the communal celebration, a work that was forced to sprout its roots from the land and consciousness that is Canada. It’s considered now as “Canadiana” for reasons that are mostly made-up. There’s surely more to this arbitrary association, and I asked Sergio how he identifies with this capacity to invent the “self.”

“With the deterioration of contact I had with my native country and culture, I had to invent culture,” Sergio revealed to me. “Sometimes there were periods in my life when I started forgetting to say things in Spanish. That was scary, losing your language. When I went to teach in Mexico, I already had been here in Canada for eight years and had nobody to speak Spanish with. And so I had a lot of problems teaching electronic music at the National Conservatory. I had to invent my own culture—folklore, traditions, sounds, reasons—from all memories and influences I had…things that sound like they might have come from Cuba but, of course, didn’t.” That particular thought is too significant not to miss: a metaphysical aspect of culture emerges where actors rely on mere impressions of familiarity in order to reproduce a resemblance of itself.

While Jitanjafora never employed a direct, literal translation of Mariano Brull’s poetry, the progression of sound events and orchestral swelling (scaffolding, at the very least) allows a perceived passage of time that mimics the angled jarriness of syllables, jammed together to string along a series of clumsy words. Acoustic sound colours come in contact with sound processing and synthesis, as the electric violin, a MIDI controller, and effects processors including the Yamaha SPX1000 and a Roland SE-50 trigger programmed sound samples. Robert Everett-Green described the work as an “anti-concerto,” and upon closer scrutiny, one would ask if the orchestra genuinely accompanies the violinist, or if they inhabit and serve the sound worlds of the processed sounds instead.

This clumsiness requires a degree of compensation for Jitanjáfora’s audiences—meanwhile, Dorothy’s parents back in suburban Chicago had to compensate in maintaining a sense of Chinese culture at home through language, education, and traditions to the best of their ability. “Life at home was in great contrast to, and at times in conflict with, my experience at school with my Midwestern American classmates,” Dorothy wrote in an email. Along with learning Mandarin and rebelling against it, communicating with grandparents was also difficult with thick Shanghainese accents in one familial side and a Jiangxi one in the other. “At home, eventually my family settled into a ‘Chinglish’ dialect, which is what we use to converse even now.”

Inventing new modes of communication comes as a coping mechanism, where the home becomes a site for reconfiguring and codifying not only physical spaces, but also mental spaces under the context of sustaining morphed identities in the midst of survival. This, I believe, is what Sergio’s Jitanjafora signifies.

Traditions and imagined anthropologies

“Othering” also comes into play within the process of integration and assimilation. Reinventing oneself requires the perpetual demand of questioning which parts of the self fit in and which parts do not. This aspect of the unfamiliar and the strange is a point of contention for Montreal-based composer Gabriel Dharmoo, born in Quebec from a Trinidadian-Indian father and a Quebecois mother. While visiting his apartment in downtown Montreal, I asked Gabriel whether his affinities with his mixed background also need inventing.

Photo of composer Gabriel Dharmoo.

“I feel almost more comfortable with Indian culture than Carribean culture; my relationship with the former is speculative, whereas relations with the latter are tangled and I perceive them as somewhat unsalvageable,” he told me. “[Inventing affinities] is part of identity formation…it’s definitely not real, but it’s also tangible and meaningful. It’s fraught with a lot of [complications]…I’ve taken up Indian music, had lessons, and done research on it. I never really thought to focus on it to the point of becoming a specialist because of how uncomfortable I was with feeling fully [placed] in that.” Gabriel also met Soosan Lolavar recently in an April 2019 conference in Turkey. An Iranian-British performer who delves into experimental santur, she told him how loaded and complex it still is to navigate in using the traditional instrument for her artistic practice. “I think when you’re bicultural,” Gabriel comments, “you’re inventing this affiliation [with cultural traditions]. But it’s never simple. That’s something I feel that people should be conscious of when they engage with another culture as a specialty. For them, access may be easier in many ways,” he concluded with a laugh.

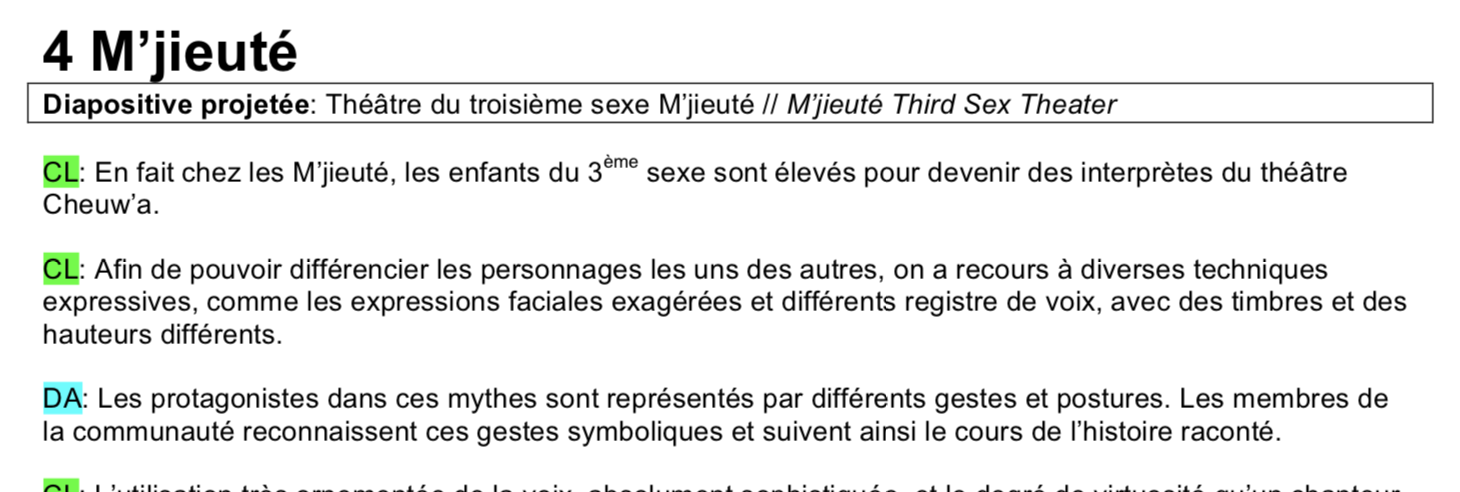

Addressing the complexities within this kind of engagement brought him to create Anthropologies Imaginaires. Jason Blake wrote that the staged work “…bears a broad smirk beneath its deadpan mask of academic seriousness[,] and it humorously questions the ways in which Western society judges and defines otherness, and packages it for consumption.”6 Here, one witnesses a series of vocal chant performances on stage—sometimes vocally acrobatic, sometimes just plain otherworldly—paired with video commentaries of seemingly well-informed experts, exactly depicting the ethnomusicological practice found within the sphere of musical academia. Operating under the framework of humour and satire, the work ends with the revelation that the commentaries are dubious; the people posing as experts are not the authority figures they project at all. Gabriel plunges us into the world of myth-making and deciphering as he told me that, “this idea of invented traditions is more centered around what’s fiction and what’s reality.” We then ask: which information here is proven to be true? Which ones are half-truths? Which ones are fabricated and are just funny to watch? More importantly, what are the intentions of showing them in public? How do we negotiate with them? Am I laughing at the expense of systemically-othered peoples, or should I laugh to show that I recognize how hilariously outrageous it is to act as ourselves, as passive audiences who form uneducated judgments?

An excerpt of the mockumentary script from Dharmoo’s Anthropologies imaginaires. Depicting a fabricated theatrical form of the third sex among the (non-existent) M’jiueté people, Catherine Lefrançois (CL) and Daniel Anez (DL) act as pseudo-experts in the video commentary while Dharmoo acts out the tradition onstage.

Another excerpt of the script where Alexandrine Agostini (AA), Florence Blain Mbave (FBM), and Luc Martial Dagenais (LMD) appear in the video screen to explain Dharmoo’s grunts and vocal spasms onstage as a man’s ‘preventive exorcisms after sexual activities’ among the fictitious Sviljains.

As much as invented folklore existed in various parts of the world for many reasons, constructing the composer-performer as the site itself of embodying fabrication puts Gabriel in a unique platform of empowerment. Being subjected to certain labels as he forged his artistic career, his position through Anthropologies Imaginaires appears not only to critically question social impositions and nuanced engagements with cultural diversity, but also to liberate himself from patriarchal and colonial mindsets that fuel such impositions. For him, the practice of invention as fabrication becomes a tool to untangle subtle oppressions out of social unity and belonging within a diverse landscape.

Lost and found within small, curious places

Luckily, Dorothy didn’t need to invent her own traditions to cultivate belonging. Chinese communities and cultures found their way out into the world, effectively establishing Chinatowns and enclaves in numerous cities. But even with the migration of culture, exposure to Chinese music as a suburban Illinois native was minimal. Her mother tried her best to fill in the gap. Dorothy wrote in an email that, “the folk songs my mother tried to teach us were more significant, not so much the music itself but what it represents—the attempts of my mother to ‘salvage’ and pass down something concrete from our Chinese cultural heritage.” She only felt impact in gaining more exposure during her studies of Chinese music in Indiana University and Nanjing University, if only to gain “a form of greater awareness of [her] lack of knowledge, understanding, and cultural connection to traditional music.”

Both scored for a mixed ensemble of Chinese and Western instruments, Dorothy’s works Lost and Found (2010) and Small and Curious Places (2013) make up an interesting pair. They embody manifestations of her negotiations with cultural roots and attachments, with one highlighting the polarities of two worlds, and the other allowing their simultaneous existences with reckless abandon.

“I viewed Lost and Found [both] as a challenge and an opportunity for exploration. Being my first larger work for mixed Chinese and Western ensemble, it was an issue I felt compelled to address,” she wrote to me. What was the issue here? Familiar to many Asian contemporary music composers, it’s the quintessential duality of the East and the West, the Asian and the Euro-American experience, the challenge of integrating tradition and innovation coherently that their sound worlds warrant segregation and identification to initially start making sense. This issue was not confined within the diasporic context—the Asian Composers League was born in the 1970s out of a need to interrogate issues of cultural and regional identity in contrast to the growing Western influence among emerging modernities. Chou Wen-Chung, Jose Maceda, Toru Takemitsu and other prominent composers in the East and Southeast Asian regions took the reins to negotiate collisions of polarized ways of thinking and their accompanying sound worlds. While various Asian modernities have changed throughout the decades, this challenge still resonates within the diasporic experience on the other side of the globe.

The segregation of sound worlds in “Two Gardens,” from Dorothy Chang’s Lost and Found (Copyright: Dorothy Chang).

Dorothy eventually felt compelled to move beyond the East/West discourse. For Small and Curious Places, “I instead approached the ensemble as I would any mixed ensemble; that is, to first consider the sound and characteristics of the individual instruments, how they might be used in combination, and the various sound worlds I might be interested to explore.” This is when integrationism sets in—differences need to be settled and equalized in order to enable one in moving forward. It is not a modernist collage of juxtapositions and certainly more than an elaborate form of hybridity and eclecticism; it is a postmodernist compartmentalization of identity formation. Both fragments occupy the same physical body at the same time, both play a role in how each interrelate and interact with informing the psyche, both create internal friction but also provide channels out of the ensuing conflict. They form organic intersections as much as they form non-negotiable boundaries.

The purposeful intent of accepting oneself: the integration of Chinese and Western instruments in “Love thyself,” from Small and Curious Places (Copyright: Dorothy Chang).

This comprises the internal, modular worlds of migrants and immigrants. Like ordering from a restaurant menu, one gets to choose which sensibilities to absorb and which ones to discard within one’s daily experience. Interestingly, the act of accumulating bits and pieces of foreignness expands one’s conception of self within a space that ironically wants itself to be restricted, contained, limited. With this trajectory, I revert back to the idea of the nation-state and how the social construct is sustained and commodified, so much so that it conveniently warrants its own reproduction.

Commodifying diversity within the Canadian nation-state

To help me explore this territory, I met Soma Chatterjee who’s a scholar and a professor of social work at York University. As an immigrant herself who specializes in migration and nationalism as her area of research, she seemed the perfect person to answer my question: “who and what is Canada?” Not surprisingly, she brings the conversation back into the world of myth- and construct-making.

“You have to have a vision, a constructed notion of who a Canadian is,” she started. “The idea is this Anglo-European body. There’s a particular kind of body politic that you have to fit into. It’s this Anglo-Saxon, Christian body that is envisioned as ‘the’ legitimate Canadian, and everyone else tries to move towards that centre. For everyone else, it’s a process of becoming.”

Framing labour markets within this centrality becomes prominent here. “Conditional belonging” serves as a key phrase: if the Anglo-Francophone subject is historically envisioned as “the Canadian,” the conditions for welcoming the rest into the labour market lies on factors like English and/or French proficiency, comfort with Canadian workplaces, degree of assimilation, and pace of adapting to new environments. Soma posed as an interrogator to elaborate this further: “What kind of accent do you have? Is it too thick? Are you visible in the workplace? Are you almost like some [plank] in my eye,7 or can you mix in comfortably for me so I don’t have to reach out and make an effort to understand and work with you? How quickly can you be assimilated into the structures that have worked here for a while? How is it so that we really don’t want to stretch it for you, although we construct ourselves as this welcoming, multicultural, post-national nation?”

My mind stopped in its tracks upon hearing these benchmarks. As a newcomer and a person of colour myself, it didn’t help that aiming to perform an identity resembling Canadian whiteness has been a coping mechanism to navigate Canadian spaces without being “othered” or seen as a nuisance. I asked Gabriel how his mixed background contributes to his worldview, and he responded to this in the perspective of privilege: “[As a person of colour], I don’t have trauma. Some people have trauma through encounters every day for years, so I’m a bit fortunate in that I don’t have trauma surrounding my identity as a person of colour.” For him, to see this as a source of strength should make it easier to advocate for equal access and recognition. “It’s important for me to engage with that part of my identity rather than assimilate with ways that are already strongly promoted.”

The conversation about feminism and gender parity also emerged as Gabriel noted its importance in the contemporary music scene for the past ten years. “There’s a surge of advocacy in that direction [now]. Twelve to fifteen years ago when I was a student, there were much less female composers among my peers than I see now. Now, it might not be up to 50%, but there’s more influential composers and role models who are women. They exist, they’re doing work, their work speaks, people know it’s a possibility—whereas young women in the 1980s didn’t have many models (or knowledge of their existence, as I would imagine in the pre-Internet era). If I think of it that way, it’s why I want to engage with the fact that I’m a person of colour in this scene and just not to have it being inconsequential.”

On the other hand, Soma was more conscious about potential problems with celebrating diversity. “Within the limits of [Canadian] multiculturalism, I try not to forget that diversity has become a commodity,” Soma reminded me. It’s a project of the nation, selling the idea that Canada is diverse, post-national, peace-keeping, and reconciliatory among the Indigenous peoples. It sells itself as a welcoming haven for refugees of war-torn countries—highlighting this reminds us that Canada is still functioning in a war economy as it has since World War I.8 Even post-nationalism is pursued as a nationalist project, still bound through an unrelinquished control over resources and war economic mechanisms. This is where the agenda of commodification sets in.

“Another thing I try not to forget is how all of this is tied to the political economy of capital,” she continues. “On the one hand, I think of Mahmoud Darwish, Edward Said, and other [exiled] writers [known internationally] and you’d think that art can transcend physical borders.” But on the other hand, diversity is a global concept and not a self-contained one. “There are people left behind who [embody] diversity in particular areas of the world and we forget all about them. We only focus on diverse cultures, food, bodies, or accents. And all of these constitute diversity as commodity that we benefit from!” As much as buying a Mexican burrito or a Japanese bento box with Turkish coffee and baklava for lunch is normalized in urban North America, this privilege doesn’t trickle down towards other parts of the world. We only pay attention to diversity’s accessibility within the locality, and not about the complex social landscapes around the world that materialize them on a daily basis.

Recognizing the “we” is also highly crucial here. Soma constantly refers to “we” as the nation-state “we,” the vague “we,” the “we” upon where the formation of collective memories plays a role. In this regard, Benedict Anderson makes sure that we remember the spirit of blind inclusion in these imaginings. But as much as imagined communities work on a national level, compartmentalizing other parallel localized imaginations run amok without any means of reconciling it within national boundaries.

To emphasize this, American writer Bharati Mukherjee made the distinction between the conditions of expatriation from that of exile. In her essay “Imagining Homelands,” she pulls out unique analogies to do so: “if expatriation is the route of cool detachment [from the homeland], exile is for some that of furious engagement.” Her recollections of living in Canada with writer and husband Clarke Blaise include “daily contact with the passions of pro- and anti-”Colonels” Greek immigrants in Montreal” during 1967, along with the threats of arson by pro-junta Greeks on anti-junta businesses. Even Torontonian and Vancouverite communities had their troubles: “…the early years of the Punjabi civil war [in the 1970s] were playing themselves out on the streets of various Little Indias. In all cases, police response, despite appeals for protection by what are called in Canada ‘visible minorities,’ and by simple Canadian citizens such as myself, harassed on the streets and in public transportation by white youths, was a variant of ‘It’s not our [meaning white, Canadian] problem. You guys’—or more likely, you little people—’settle it among yourselves.’”9 With numerous perceived barriers, the difficulty of establishing her presence in the scene in spite of their newly-acquired Canadian citizenship and the success of The Tiger’s Daughter (1971) elicited strong provocations from her that led them to leave Canada in 1980.10 These disruptive narratives take place within compartmentalized imaginations, safely tucked away from the white experience of the Canadian majority.

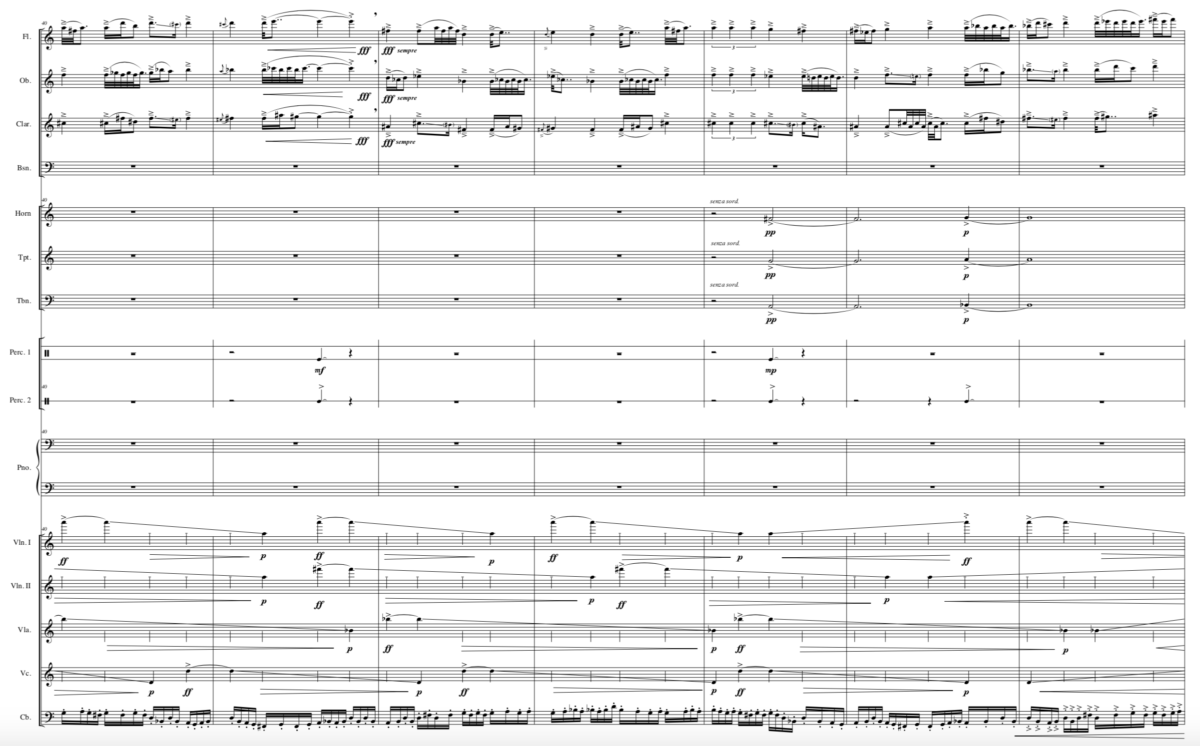

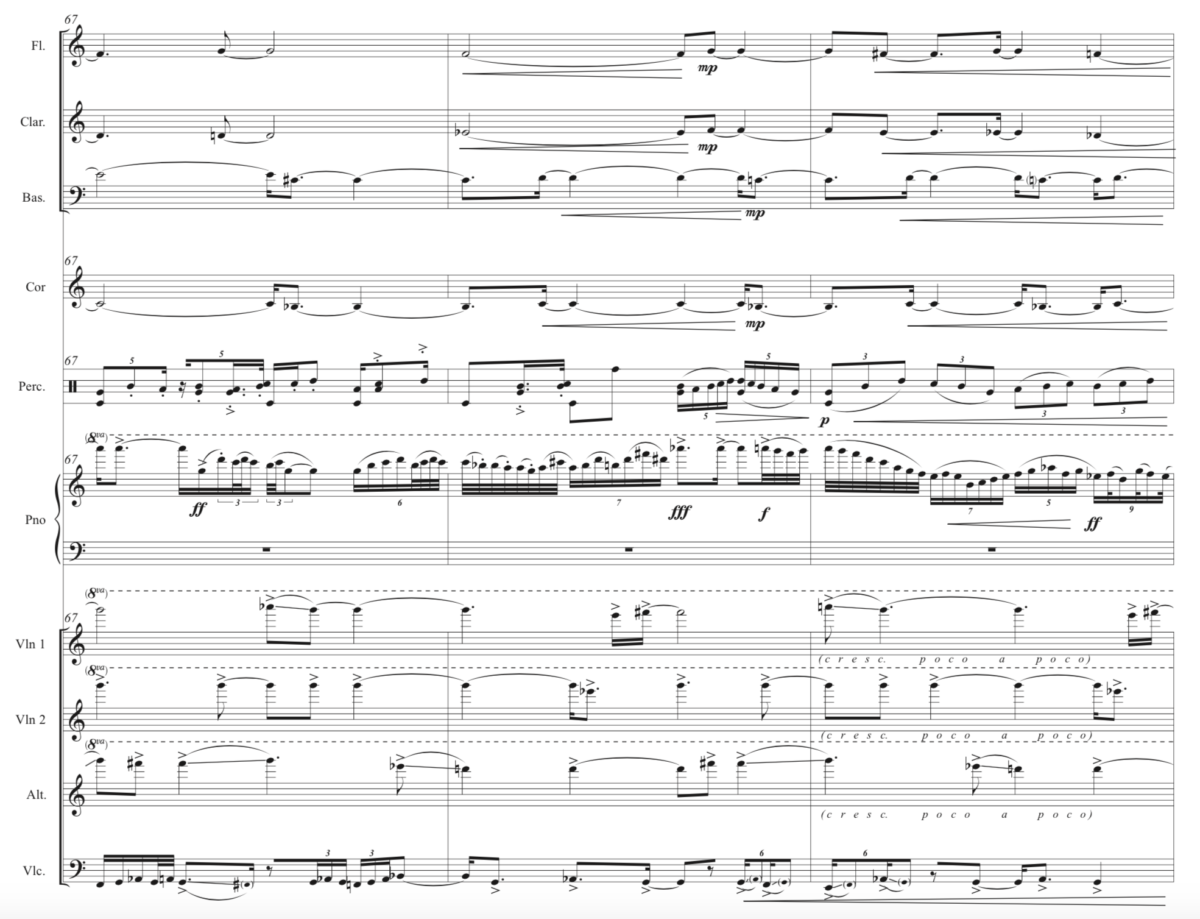

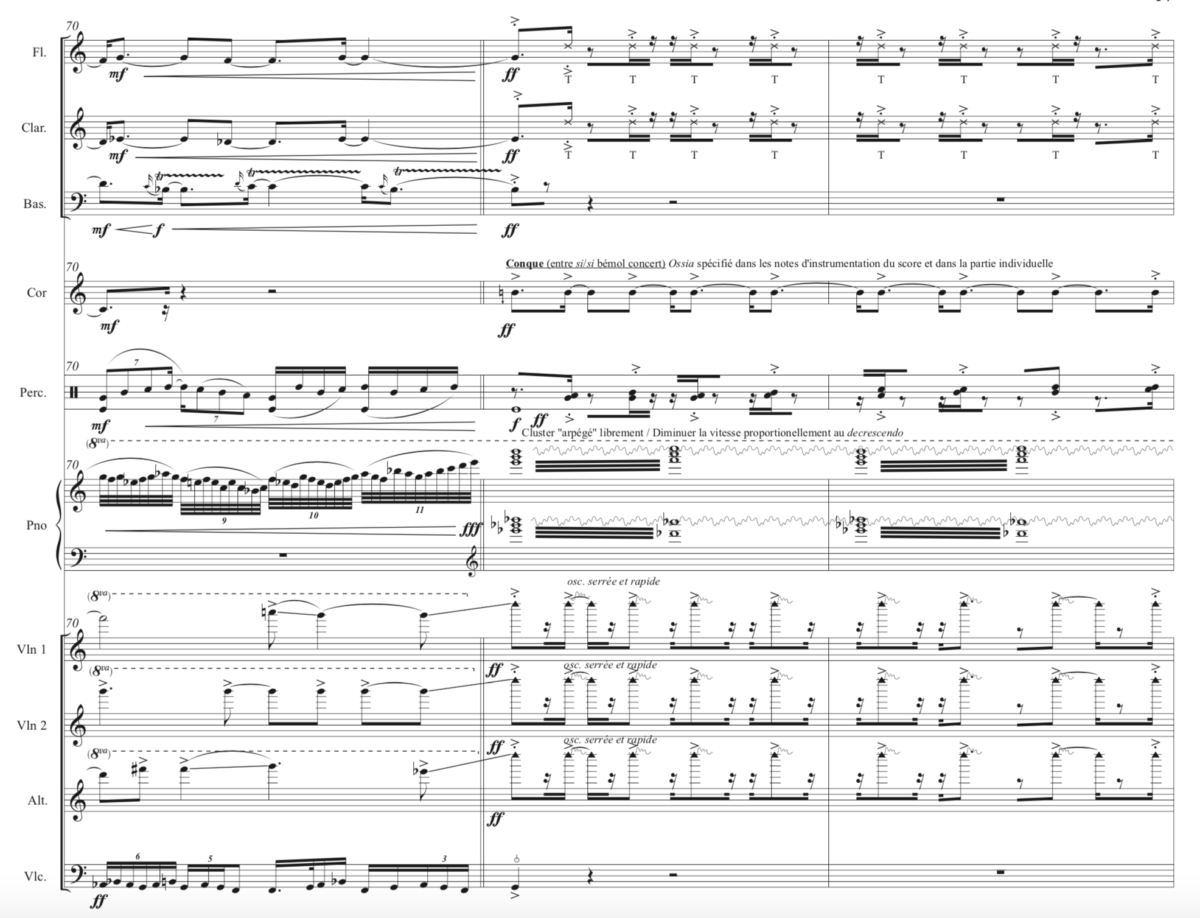

Exposing these facets of residing in Canada reveals the perceived pettiness of minority life existing within national borders. Even while glaring at the face of otherness, allowing art to assert identities can also be uncomfortable for Gabriel as a Canadian and a Quebecois. Since composing works like Moondraal Moondru (for chamber orchestra, 2010, rev. 2013) and Ninaivanjali (for 10 instruments, 2012), he felt that his artistic direction would be tokenized and steered towards trajectories he wouldn’t have control of. He told me that, “for a while after I came back from India [to study Carnatic music in 2008], I was integrating Indian music influence more overtly, and I thought, ‘Oh, I felt uncomfortable with that.’” Elaborating further in a 2019 article, he learned that erroneous perceptions of cultural and musical practices emerged among listeners and audiences relating to his work. This discomfort comes from the unnecessary burden of representation, the expectation that one functions as an entry point for curiosities deemed inaccessible. “I felt that there will be assumptions made not just on my work, that it would become a reference point for a whole musical system…So I would veer off this way, dispel things that might have been [assumed of me]. If people thought I was this ambassador of Carnatic music in Canada, I’d say, ‘no, not really!’”

Program notes of Gabriel Dharmoo’s Moondraal Moondru.

The flute, oboe, and clarinet take centre stage in “Trio bois,” the first tableau of Moondraal Moondru. (Copyright: Gabriel Dharmoo)

And rightfully so, with the subsequent conception of Anthropologies Imaginaires and its emphasis on coloniality and post-exoticism. These works serve more as glimpses of journeys navigating through creative labours and processes, not representational markers of otherness. With Moondraal Moondru, the Carnatic musical ragas and a linear formal structure reflect not only the sound worlds which Gabriel was immersed in, but also the act of forging personal connections and involvement in “de-othering.” Harbouring a final section that leans on the Shree raga section from Patnam Subramaniam Iyer’s Navaragamalika,11 Ninaivanjali12 is dedicated to his teacher N. Govindarajan who passed away in May 2012. These pieces aren’t musical works that signify otherworldly existences—they simply tell strands of stories involving people.

Even when rendering an exposition of a raga in Ninaivanjali, the piano as a soloist wittingly creates ambiguity with the role’s semblance within jazz music making. (Copyright: Gabriel Dharmoo)

Becoming a Canadian, becoming an insider

But if highlighting diversity comes at the cost of its commodification, what about the stories that propel multiple trajectories of differences among those living within confined borders? With the vastness of human experience, would this omnidirectional dispersal cause the death of collective memory, of national consciousness?

Take the case of Sergio’s long-winded journey to Canada. After extracting himself from Cuba, he travelled in Europe and tried settling in France. “Everything was fine,” he related, “but one day after I applied [for legal residence], I had the bad idea of going to the immigration office in Champs-Élysées and inquire about my application.” An officer misinformed him that he would be automatically sent back to Cuba if the application was denied, which he found later was incorrect. “First of all, it was automatic only if I have a criminal record. Secondly, by a resolution of the United Nations, France couldn’t send somebody from the Eastern bloc back.” But false information sent him underground in Paris because of the awareness that Cubans figured out where he was.

“I left for Belgium, but they also figured that out. I tried to stay there—I had many friends, I had many opportunities in Ghent.” But pursuing a musical career in Belgium required having citizenship, as everything is paid for by the Belgian state. “And to get citizenship at that time was [equivalent to] 17 years of residency. I don’t have a chance, but in that moment came the opportunity to come to Canada through connections.” In contrast to Sergio’s familiarity with Czechoslovakia and the European Eastern bloc, Canada was unknown territory for him. Even while family relatives made him to consider Miami, there’s apprehension in residing in the United States as someone coming from the communism of Cuba. The hustle came to a point when RCMP Security Service detained him after applying for permanent residency in Canada. The reason: his involvement with the State Counter-Intelligence Service, an enforced proposition for Cuban artists which has dangerous consequences if they reject or say no.

Sergio continued the story: “A car came with two civilian-dressed [RCMP] Security Service officers. They arrested me and took me to a nice hotel near Ottawa, and I was interrogated there for about three days. Finally, one question came: ‘if you have all your aunts, cousins and your grandmother in Miami, why did you want to come to Canada where you practically know nobody?’ I said, ‘I don’t want to go to the US because I don’t like the US,’ and I thought that will disqualify me [from anything], but the guy stood up, shook my hand, and said, ‘neither do we!’ And so a few days later, they sent me back and said that my residency is granted. I can do whatever I want.”

Dorothy also had her share of difficulties as she tried settling in Canada. Rewinding the story back, she met flutist and future-husband Paolo Bortolussi while studying at Indiana University. They became romantically involved, got married, and looked for options to build their professional careers together as artists. “[Paolo] is Canadian from Halifax, and we were just looking for anywhere where both of us could find meaningful work,” she told me. Relocating then was more about convenience—Dorothy applied for a professorial position at the University of British Columbia and got accepted for the role in 2003. “Honestly, I really didn’t know much about UBC [at that time], and he’d never really been out West. I remember the first time he went to Vancouver, I had already accepted the job and had to bring him in [the city] and ask, ‘So what do you think?’”

The initial excitement turned into confusion when her professorial appointment elicited an uproar among Canadian academic and artistic circles. Dorothy recalled that time: “It was a shock when one morning my mother-in-law called and said, ‘You’re in The Globe and Mail!’ And there was that big write-up about UBC hiring an American.” The article in question pulled up statistics on academic foreign hires: McGill University with 61% for 2004, University of Toronto with 49% for 2003, University of British Columbia with 38% for 2003, and University of Alberta with 30% from 1999 to 2003.13 A dialogue of letters to the editor followed suit, including those from composers John Burge and Janet Danielson who raised suspicions that hiring committees “did not follow legislated hiring practices set out by Human Resources Development Canada.” In a 2004 newsletter issue of the Institute of Canadian Music, musicologist Robin Elliott wrote that the conflict of interests regarding a push for diversity while prioritizing Canadian citizenship within academic hiring remains a subjective point of contention, seemingly resulting in “abundant possibilities for circumventing the spirit, if not the letter, of the HRDC regulations.” But while citing his own appointment as a non-Irish faculty at the University College Dublin demonstrated Article 45 of the European Union Labour Law,14 such citation doesn’t remove the requirement that one should belong to a specific member state (hint: Robin Elliott holds dual Canadian/U.K. citizenship).

Dorothy expressed both frustration and humour in her situation: “With the lack of a very firm connection to any particular culture…it was almost shocking to me to be labelled as strongly as ‘American.’” She never felt as American as she did upon arriving in Canada—the whole time she lived in the United States, she was always labelled as “Chinese,” a “foreigner.” But the reliance on publicly-funded institutions as stewards of maintaining a welfare state still enables this othering, as much as both Sergio and Gabriel, among many Canadian artists, now rely on arts councils as rightful Canadian citizens to obtain government financial support in the name of Canadian arts.

The limits of citizenship

While civil rights generally apply where humanity’s existence demands it, these rights are granted under the jurisdictions of state constitutions that conceived them. Human rights are different—these are recognized simply by being human. Political scientist Aoileann Ní Mhurchú highlighted this persisting separation between the “citizen” as a political entity and “Man” as human,15 giving us the opportunity to imagine a hypothetical scenario: a migrant mother, a non-citizen of whatever country pops in mind, giving birth to a child. The underlying question then would be, “Is this child now a citizen of that country?”

The answer: it would depend on the country’s constitutional provisions. The concept of jus soli (citizenship based on birthplace), had its own history of rippling disruptions with examples in Britain (1981) and France (1993) that saw conditional provisions depending on their parents’ residential status or the subject’s declaration of intent, respectively.16 Bear in mind that many European countries follow the principle of jus sanguinis (citizenship conferred from a parent by birth), but children subjected to these amendments were deemed “potential citizens”—not full citizens but neither merely migrants. Rather than a clear-cut definition, they fall between being defined in terms of the state as citizens, and in terms of humanity. As Rainer Bauböck problematized that the exclusivist citizenship model blindly assumes the full completeness of democracies under inclusion and equality (2006), Ní Mhurchú proposes the challenge of rethinking citizenship as ambiguous instead of fixed within binary notions of “citizen/migrant” and “insider/outsider” (2014). While focusing on cases of children born under this ambiguity, these disruptions should provide challenging interventions in how we understand political community. From rethinking the citizen as the sole constituent, it pushes beyond legal terminology towards highlighting the transitory nature of socio-political participation in current global migratory populations.

This proposition also indirectly addresses the myth that Bharati Mukherjee dispels with disdain. “With the pietistic formula ‘we are all immigrants,’” she started, “I have to disagree. We are not, and never were. We have reinvented the myths of our founding so many times, and for so many audiences, that we’ve probably lost all trace of a unifying narrative.”17 Soma translated this in the Canadian context: “The idea of ‘everyone is an immigrant’ has been mobilized for the nation-state to delegitimize thousands of years of Indigenous history and governance in this part of the world.” Otherwise, if everyone is assumed to be a settler-immigrant, one’s claim to the nation-state is quickly solidified especially for Anglo-Francophone subjects who colonized the land. Besides the undeniable Indigenous presence that problematizes Canada’s conception of the “citizen,” Soma concluded that, “everyone’s experiences and trajectories can’t be captured within the idea of settlerhood. People had different ways and histories that brought them here, and that needs to be acknowledged.”

At the same time, the Canadian labour market further reaffirms Anderson’s proposition that the nation-state is limited. Soma wrote that establishing “Canadian experience” as grounds for labour market regulation and immigration policy establishes claims of “epistemic superiority” of the White European body politic. While this thinking reconciles a non-negotiable immigrant presence, it sees such presence as detrimental to national identity as it seeks to conflate the politics of national membership with discourses of skill and labour.18 In this sense, artistic circles who conform to a limited, exclusionary exercise of nationhood contradicts the very grounds where liberal multiculturalism and diversity supposedly thrive. In the case of Dorothy’s quandary, her process of becoming “Canadian” was tainted and superseded with a false conception of fixed positions that instead focused on her otherness as detrimental to Canadian society. Even more so, the necessary condition of “becoming Canadian” reinforces the myth that the mostly predominant white Canadian is superior and desirable not only as a worker subject, but also as the sole, valid participant among Canada’s political imagination. The otherness has to disappear first—at the same time, social order prevents that very first step to trample that otherness.

But it doesn’t stop with Dorothy’s appointment. Public institutions are accountable to prioritize the welfare of citizens and permanent residents, as expressed in the letters to the editor of The Globe and Mail. Arts councils demonstrate this provisionary inclusion/exclusion in their mandate, where only artists who are Canadian citizens or permanent residents are granted access to public funding and support. Organizations who espouse the prestige of national agenda in the arts sector like the Canadian Music Centre exercise a similar exclusionary approach towards its associate composer membership. The fact that ethnic diversity has been significantly absent in Canadian music historiography of the 1980s19 brings us back to institutional protectionism and feudalism, denying not only the humanity of marginalized communities, but also potential opportunities that this multiplicity could have generated. Bearing current narratives of Canadian citizenship in mind, the hegemony bestowed on the prevalent Anglo-Francophone body politic has to continually dissolve in order to reveal various threads of network flows involving artists residing in the nation-state within various capacities and positionalities—even within various state-regulated restrictions and privileges—to participate in socio-political communion. As the exclusivist “Canadian” among artistic communities loses its meaning in terms of territoriality and sovereignty because of transitory and migratory trends, the ambiguity should redefine what the “Canadian” entails.20

With the undeniable notion that citizenship is a socio-political construct—a fabrication to ensure communal protection—let this invoke reinvention, shifting from weaponizing a singular Canadian political imagination towards diffusing multifaceted trajectories that render Canada as a site for continuing experimentation on postnational imaginations. With Dorothy, Sergio, and Gabriel, these imagined and invented places were first conceived in their minds in the same way that music first emerged in the deep recesses of one’s musical worlds.

1 Omar Aziz, “The Raptors Win, and Canada Learns to Swagger,” New York Times, June 14, 2019, accessed June 17, 2019, URL.

2 It is worth noting that Hong Kong’s crisis with the formulation of the Extradition Law (2019) becomes a present case demonstrating resulting tensions between the Hong Kong population and the Beijing government under the One-China Policy, once stretching it to a “One country, two systems” as the British crown officially ceded the territory back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997. Current fear holds that with the passing of the law amendment, mainland China can freely exploit its powers to extradite Hong Kong residents accused of any criminal activity, be subject to mainland China’s judiciary, and effectively bypassing the “One country, two systems” principle on an unofficial basis.

3 Robert Everett-Green, “Losing sight of the show,” Globe and Mail, February 1, 1994.

4 William Littler, “Brave Esprit Orchestra uncorks 5 original works,” Toronto Star, February 1, 1994.

5 William Littler, “Esprit Orchestra season opens with Canadiana,” Toronto Star, October 24, 1995.

6 Jason Blake, “’Anthropologies Imaginaires’ review: A wry look at the world via its weirdest music,” Sydney Morning Herald, January 10, 2017, accessed June 26, 2019, URL.

7 Soma Chatterjee post-interview (October 2019): “I think of ‘being sand in the eye’ to capture, rather unsuccessfully, the feeling of discomfort that different bodies bring to the workplace or social spaces.”

8 Wartime Canada provides a catalogue of online documents that shows how the World Wars have shaped the Canadian economy and society. See http://wartimecanada.ca.

9 Bharati Mukherjee, “Imagining Homelands,” in Letters of Transit: Reflections on Exile, Identity, Language, and Loss, ed. André Aciman (New York: New Press, 1999), 75. Brackets are mine.

10 John Barber, “Clarke Blaise and Bharati Mukherjee: a shared literary journey,” Globe and Mail, June 15, 2011, accessed July 19, 2019, URL.

11 A “navaragamalika” is a musical piece that strings together different ragas, one after the other.

12 The program note states that “ninaivanjali” is a Tamil expression meaning “in memory of,” used to pay tribute after someone’s death.

13 Caroline Alphonso, “Foreign hires sweet music to universities,” Globe and Mail, May 11, 2004, accessed May 24, 2019, URL.

14 Article 45, Section 2 states that the freedom of movement entails abolishing any discrimination on employment based on nationality between workers of Member states.

15 Aoileann Ní Mhurchú, Ambiguous Citizenship in an Age of Global Migration (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 47.

16 Ní Mhurchú cites two amendments in French and British law: (1) the provision in the 1993 “Pasqua law” which amended simple jus soli in France, making it dependent on a declaration by the child in question at the age of majority; and (2) the 1981 British Nationality Act which made citizenship at birth conditional on having a British citizen parent or a parent who was settled in Britain. See Ambiguous Citizenship in an Age of Global Migration, 34-35.

17 Bharati Mukherjee, “Imagining Homelands,” 84-85.

18 Soma Chatterjee, “Skills to build the nation: The ideology of ‘Canadian experience’ and nationalism in global knowledge regime,” Ethnicities 15, No. 4 (2015): 555.

19 Beverley Diamond, “Narratives in Canadian Music History,” in Canadian Music: Issues of Hegemony and Identity, eds. Beverley Diamond and Robert Witmer (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1994), 149.

20 Additionally, the climate change crisis puts a wildly different but relevant interruption in rethinking such notions. Land masses will disappear along rising ocean tides, and the change in biodiversity will drastically alter livelihood and resource abundance. People will find themselves displaced once again. As artistic communities reflect on the volatility of political borders, this crisis does not only challenge social norms that render themselves disposable to artistic practice, but also with geopolitical and legal structures that control the global distribution of resources.